The duality of Michael Godard

“He Devil, She Devil – Devil’s Tail” (2015), Michael Godard

For Michael Godard, it’s all in the details.

People tend to operate left brained (favoring logic, analysis and mathematics) or right brained (favoring creativity, intuition and arts). Godard, however, has combined these seemingly opposing sides to create a detailed world full of olives, alcohol and laughter.

“Even though it’s all sort of silly fun, in my world it’s very organized,” he says. “There is that technical part of me that wants everything very exact, and then there is the other part of me that is the playful side where I want to do something that photography can’t do.”

Prior to becoming an artist, Godard worked as a mechanical engineer for 12 years. His rock star look and attire began as a way of escaping the engineering world and its suits and ties, but he admits that his appearance helps hide that he is a “nerd” in disguise.

“Most of the books that I read are really boring because I love math as much as I love art, so I love to read books on physics and cosmology,” he says.

As chaotic as his images may seem, engineering and exact compositions are critical to Godard’s art and can be seen in his attention to detail and clean, polished style. Even his signature hints at the left and right brain working together: He prints his name like a draftsman, but adds flair by signing with an olive for the ‘o.’

By blending his attention to detail with his creative side, Godard tweaks his paintings with reality-based details and artistic license, creating compositions that beg to be examined. The obvious examples are the anthropomorphic olives and strawberries that are both lighthearted and emotive, but his technique is actually more subtle than that.

“If I’m painting a martini glass and the light is coming from the upper left-hand side, I will purposefully light the right-hand side because there is a place I need someone’s eye to go,” he says.

He loves the fact that an artist has the ability to control what a viewer experiences with their composition. In showing off his geeky side, he compares it to the science-fiction show “The Outer Limits” and its famous introduction: “For the next hour, sit quietly and we will control all that you see and hear.”

“It seems very similar to science and how people look visually when they’re observing a painting,” he says. “I can control where someone’s eyes go into a painting, and knowing that, I design paintings that way, so I have a very scientific approach to it.”

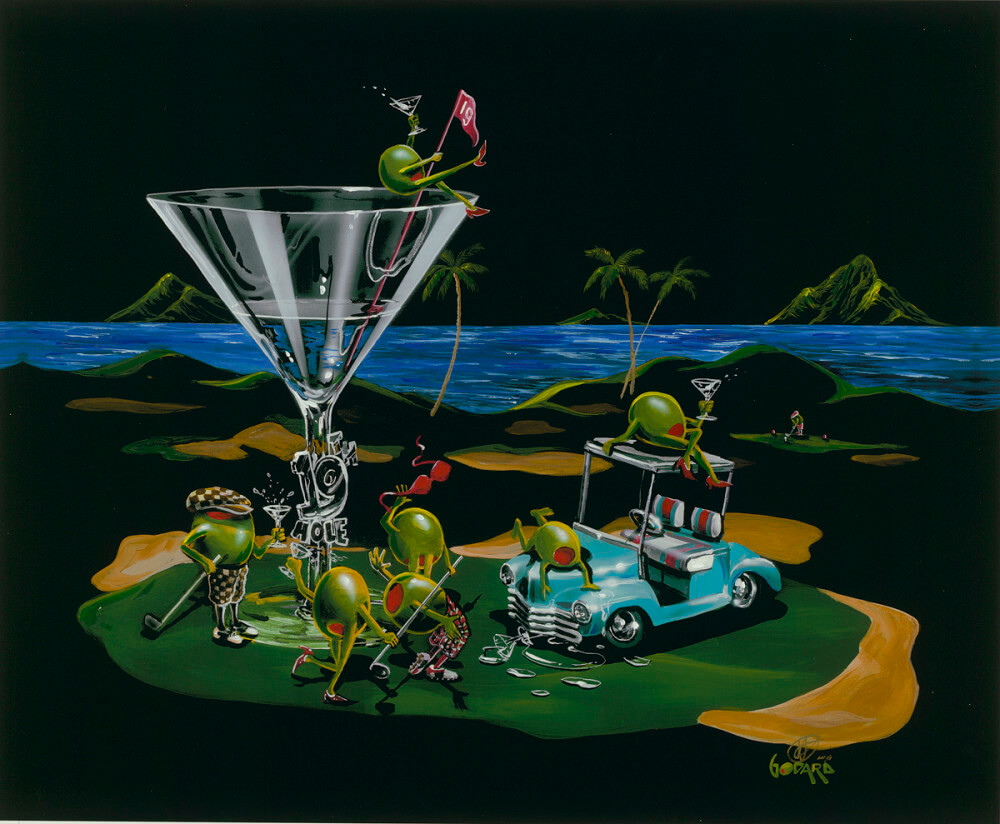

“19th Hole Water Bound” (2015), Michael Godard

A prime example is his “19th Hole Water Bound.” Notice how the golf cart leads the eye to an olive that is gesturing to the stem of the martini glass, which in turn trails up the glass itself. From there, the red 19 flag points back toward the golf cart. Godard credits this cyclical movement to carefully using triangular shapes throughout the composition.

“Everything is not just placed by accident, it is placed very purposefully where it is,” Godard says.

Even with all the details and forethought that go into his works, Godard doesn’t take himself seriously. Instead, his goal is to make his art accessible and for people to feel good when viewing it – regardless of whether they’re left or right brained.

“Someone can look at a painting, and I don’t know the reason that they’re drawn to it, but if it moves them in some way there has to be some reason,” he says. “I love that part of it, that people give it meaning.”