Scientists discover “chemical fingerprint” of Picasso

University of Barcelona along with Museu Picasso experts analyze “Man With a Basque Hat” (1896). (Photo courtesy of ArtNet, Museu Picasso/Universitat de Barcelona)

Studies of early works by Pablo Picasso have provided new insight into the renowned artist and how he painted between 1895 and 1900.

According to ArtNet News, Spanish chemical engineer Dr. José Francisco García Martínez of the University of Barcelona collaborated with the Museu Picasso to analyze art from Picasso’s early period prior to Cubism.

García Martínez used spectronomy – non-invasive studies based on light – for his analysis. He compares it to how the chemical composition of planets in outer space can be determined based on the light they reflect.

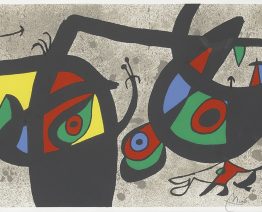

The studies were able to identify everything from a white zinc-based pigment named “Chinese white” to the composition of Picasso’s dark primers. By doing so, Picasso’s early works can now be classified in chronological order based on objective data.

The analysis even shows evidence of different images or drafts on a canvas. X-rays of Picasso’s “Self Portrait With a Wig” (1897) show the artist originally painted the subject with a large hat, while his “Man With a Basque Hat” (1895) was painted on a used canvas that depicted pigeons.

The paintings that were examined included “Retrat de Vell” (Portrait of an old man), “Man with a Benet,” “Self-portrait with Wig,” “Portrait of Carles Casagemas,” “Retrat d’un desconegut (Portrait of a stranger)” and “Head of a Man in El Greco Style.”

García Martínez’s findings not only offer insight into Picasso’s artistic process, but adds to the field of verifying artwork. The chemical fingerprint of an artist, like real fingerprints, is unique, meaning it may become easier to determine whether a work of art is authentic or a forgery.

“This chemical fingerprint is unique to the painter and allows us to characterize him. It is not only about the materials used but also about traces, which for example give us clues about where Picasso bought his pigments. This is a solid scientific basis for research,” García Martínez explained.

García Martínez concludes that the findings are significant, but there is still plenty to discover and questions to answer.

“That’s the way it is in science. When you answer a question, the answer raises even more questions,” he said.

Science and technology continue to improve studies in the art world. For example, modern tools and techniques helped end a decades-long dispute that a Rembrandt painting is authentic and not painted by one of Rembrandt’s pupils.

For more about science and art joining forces, read what astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson and artists like Peter Max have to say about the subject.