The Inside Story Behind Rembrandt’s 8 Amazing Millennium Etchings

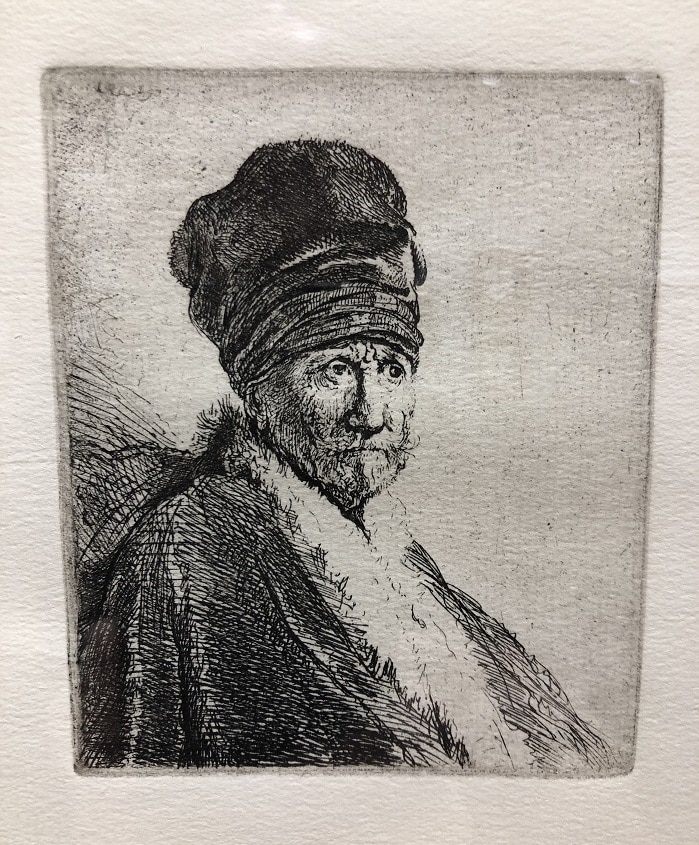

Detail from Rembrandt’s 1630 etching “Bust of a Man Wearing a High Cap; Three-Quarters”

Even centuries after his lifetime, Rembrandt’s etchings are still considered some of the finest examples of the medium. His innovations to the art of etching would go on to influence Goya, Picasso, Chagall, and generations of artists to come.

Following Rembrandt’s passing in 1669, his remaining copper etching plates virtually stayed intact as they passed from collector to collector until 1993 when a sale at the London Original Print Fair dispersed the plates around the globe. The UK Independent, at the time, described the plates being sold as “like chips off the True Cross.”

Following the 1993 sale, collector Howard Berger acquired eight of the plates. He then teamed with master printers Emiliano Sorini and Marjorie Van Dyke to pull impressions from Rembrandt’s original copper plates.

The edition was limited to only 2,500 impressions of each image, pulled over a ten-year period in the last decade of the 20th century, which is why it has become known as the “Millennium Edition.”

Today, Park West Gallery owns all eight of the Millennium Edition plates, which are now on extended loan to the North Carolina Museum of Art.

While their beauty is undeniable, the eight Millennium etchings also give fantastic insight into Rembrandt’s personal life and what it was like to live in the 17th century.

Join us for a look at eight of Rembrandt’s finest etchings and the inside details that inspired their creation:

“Landscape with a Cow Drinking” (ca. 1650)

“Landscape with a Cow Drinking” (ca. 1650)

It is believed that, in this peaceful pastoral image, Rembrandt combined the landscape in the foreground—showing the countryside surrounding Amsterdam—with a series of mountains in the distance taken from a location hundreds of miles away.

To achieve the atmospheric quality found in this etching. Rembrandt employed very delicate linework created with a fine-etching needle.

Around the time of the creation of this etching plate (ca. 1650), Rembrandt’s financial status began to deteriorate and grow desperate, and he was unable to make his mortgage and tax payments any longer. Scholars often suggest that this etching and other landscapes of the period may reflect his desire to be transported to peaceful and idyllic places far away from the troubles in his life.

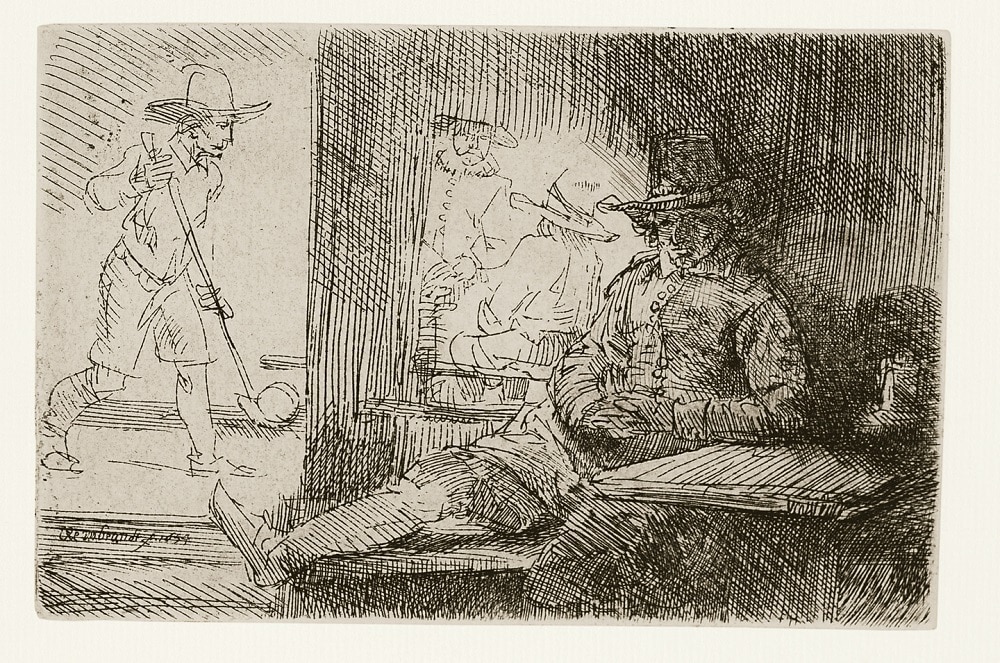

“The Golf Player” (1654)

“The Golf Player” (1654)

The 17th-century game “Kolf,” which lent its name to the modern game of golf, was extremely popular in Rembrandt’s lifetime. Rembrandt’s use of chiaroscuro in this etching—with its strong contrast of interior and exterior—reveals his ability to selectively use areas of light and shade to focus the viewer on the interior sitter.

This amusing and delightful genre scene of 17th-century Amsterdam was created the same year that Rembrandt’s mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels, gave birth to their daughter, Cornelia.

“The Artist’s Mother with Her Hand on Her Chest” (1631)

“The Artist’s Mother with Her Hand on Her Chest” (1631)

In this poignant portrait, Rembrandt captures his mother’s careworn face and tender expression as she is found in contemplation, her eyes cast downward. The position of her hand upon her chest suggests the importance of her thoughts and closeness to her heart.

The darkly etched dress and veil heighten the drama of the image, and the curve of the veil around and over her face creates an angelic effect, reinforced by the light behind.

In 1589, Rembrandt’s mother, Neeltgen Willemsdochter van ZuytBrouck, married Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn in Leiden, Holland. Rembrandt was the next to youngest of their nine children, two of whom died in infancy. Rembrandt created six etchings of his mother and several paintings of her as well. This work is an excellent example of Rembrandt’s “psychological portraiture,” where the sitter’s humanity and spiritual essence are more deeply expressed than their mere physical likeness.

“Bust of a Man Wearing a High Cap; Three-Quarters” (1630)

“Bust of a Man Wearing a High Cap; Three-Quarters” (1630)

Art historians believe that this etching depicts Rembrandt’s father, although no conclusive evidence exists that supports this belief. Rembrandt’s father, Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn, was a miller and owned a half-interest in a windmill called “De Rijn.”

In this delicate and facile portrait, Rembrandt depicts a man with a resolute jaw, earnest eyes, and a focused and intent expression, all qualities one could easily associate with the wisdom and fortitude of one’s father. The exotic and ornate dress of the sitter—wearing a turban and coat—may suggest Rembrandt’s desire to portray his father as a man of importance. His father died the same year this etching was completed.

“The Card Player” (1641)

“The Card Player” (1641)

This etching reveals Rembrandt’s mastery of depicting the character of his sitter, as the small, shifting eyes of the subject (thought to be a pupil of Rembrandt’s) express his distrust of his opponents in the card game.

“The Card Player” also represents a major step forward in Rembrandt’s experimentation with etching as he employs drypoint and burnishes to create the rich tonal effects found in the work. The extensive cross-hatching in the deep shadows behind the subject highlights the features of the sitter and enforce Rembrandt’s desire to focus the viewer on his features.

“Christ and the Woman of Samaria: Among Ruins” (1634)

“Christ and the Woman of Samaria: Among Ruins” (1634)

In this dramatic Biblical scene, created with strong shadows and contrast, Rembrandt depicts the moment that Jesus revealed himself as the Messiah to the Woman of Samaria.

According to the Gospel of John, Christ and his Apostles stopped in Samaria on their way from Judea to Galilee and rested by Jacob’s well near the town of Sychar. While Jesus was resting alone, a Samaritan woman came to the well to fetch water and Jesus asked the woman to give Him a drink. Jesus revealed that He was the Messiah and told the woman that “whosoever drinketh of the water I shall give them shall never thirst and have everlasting life.” This story is also the subject of another etching, a drawing, and three paintings by Rembrandt.

Rembrandt’s Biblical subjects comprise a substantial portion of his etching oeuvre. They have traditionally been some of his most desirable etchings amongst collectors and were innovative for their time in the manner in which they reveal Christ’s personal interactions with the people of His time.

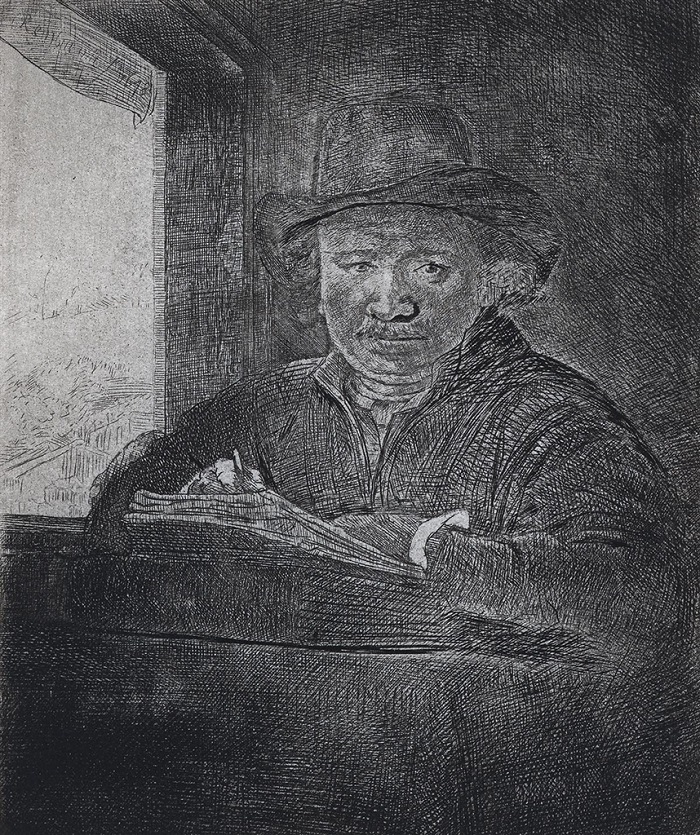

“Self Portrait Drawing at a Window” (1648)

“Self Portrait Drawing at a Window” (1648)

In 1629, Rembrandt began to paint and etch his first self-portraits. Throughout his career, he would produce many subsequent self-portraits in both mediums. However, scholars differ as to Rembrandt’s motivation for creating self-portraits.

While some have posited that he simply could not afford to pay for models, the more likely reason relates to his pursuit of “psychological portraiture.” Rembrandt used his own face in an effort to reveal the human and spiritual nature of the etching’s subject—which was a revolutionary approach for the time.

In this extraordinary image, Rembrandt depicts himself drawing at a window, as the light from the window seeps into the space and creates a symbolic dramatic contrast. Rembrandt’s face is illuminated, but the interior of the room is cast in darkness.

He created this work in 1648 at the age of forty-two, after a troubled six-year period during which he etched no self-portraits. During that time, Rembrandt’s wife Saskia died, his financial situation worsened, and his relationship with Geertge Dircx, the nursemaid of his young son, Titus, became troubled and later culminated in a court battle.

The work clearly depicts a man at maturity, contemplating his life, and suggests a wise, if not beleaguered man who has tasted life’s joys and sorrows. This was the last self-portrait ever etched by Rembrandt.

“The Raising of Lazarus: The Larger Plate” (c. 1630)

“The Raising of Lazarus: The Larger Plate” (c. 1630)

In this, one of Rembrandt’s most astonishing and powerful works, he captures the dramatic scene as Jesus commands Lazarus to “come forth” from the dead. The figure of Jesus, seen from a three-quarter back view, is against the dark tomb wall. As Lazarus rises from the dead, Mary and Martha lean in over the edge of the tomb, their upraised hands signifying their faith and readiness to embrace their beloved brother.

The faces of the onlookers express open-mouthed amazement at Jesus’ miracle. Rembrandt uses powerful contrasts in this work to evoke a heightened drama through his distinct use of light and shadow. Lazarus and the faces of the onlookers are bathed in the light of Christ, while the surrounding darkness symbolizes the blackness of death.

Rembrandt experimented greatly and labored over this work intensely, creating no fewer than ten states or variations in the evolution of the plate. It is a perfect example of the Baroque use of chiaroscuro, the strong contrast of light and shadow, to evoke a theatrical and highly emotional image. “The Raising of Lazarus” was extremely well-received by his contemporary collectors and remains one of the most sought-after etchings of Rembrandt’s oeuvre to this day.

If you’re interested in collecting the works of Rembrandt van Rijn or another master artist, please contact one of our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 during business hours or email sales@parkwestgallery.com for inquiries after hours.

The Park West Museum in Southfield, Michigan has over 20 examples of Rembrandt’s remarkable etchings on display—including examples of all eight Millennium Impressions. For more information on visiting the museum, click here.