How Rembrandt van Rijn Changed the Art of Etching Forever

Rembrandt van Rijn’s name is synonymous with fine art and a mastery of technique, but few realize that his impact on the art world has more to do with printmaking than his skills with a brush.

Sure, his world-famous paintings like “The Night Watch” and “The Return of the Prodigal Son” will forever be studied and admired, but it was Rembrandt’s remarkable innovations in the field of printmaking—specifically, etching—that helped immortalize him.

Etching, “Abraham Francen, Apothecary” (c. 1656), Rembrandt Van Rijn

THE ORIGINS OF ETCHINGS

Etching was first popularized in the 15th century, with artists such as Albrecht Dürer employing the method. The process has its origins in the armorer’s trade, where it was used to add elaborate patterns to swords and armor, but it was later adopted to mass-produce images on paper.

To produce an etching, a piece of metal known as a “plate”—initially iron, but later copper and zinc—is coated with a varnish called a “ground.” An image is then drawn into the varnish using a sharp tool and treated with an acid that eats away at the exposed metal, creating fissures. The depth and subsequent darkness of the fissures depend on the length of time the metal is exposed to the acid.

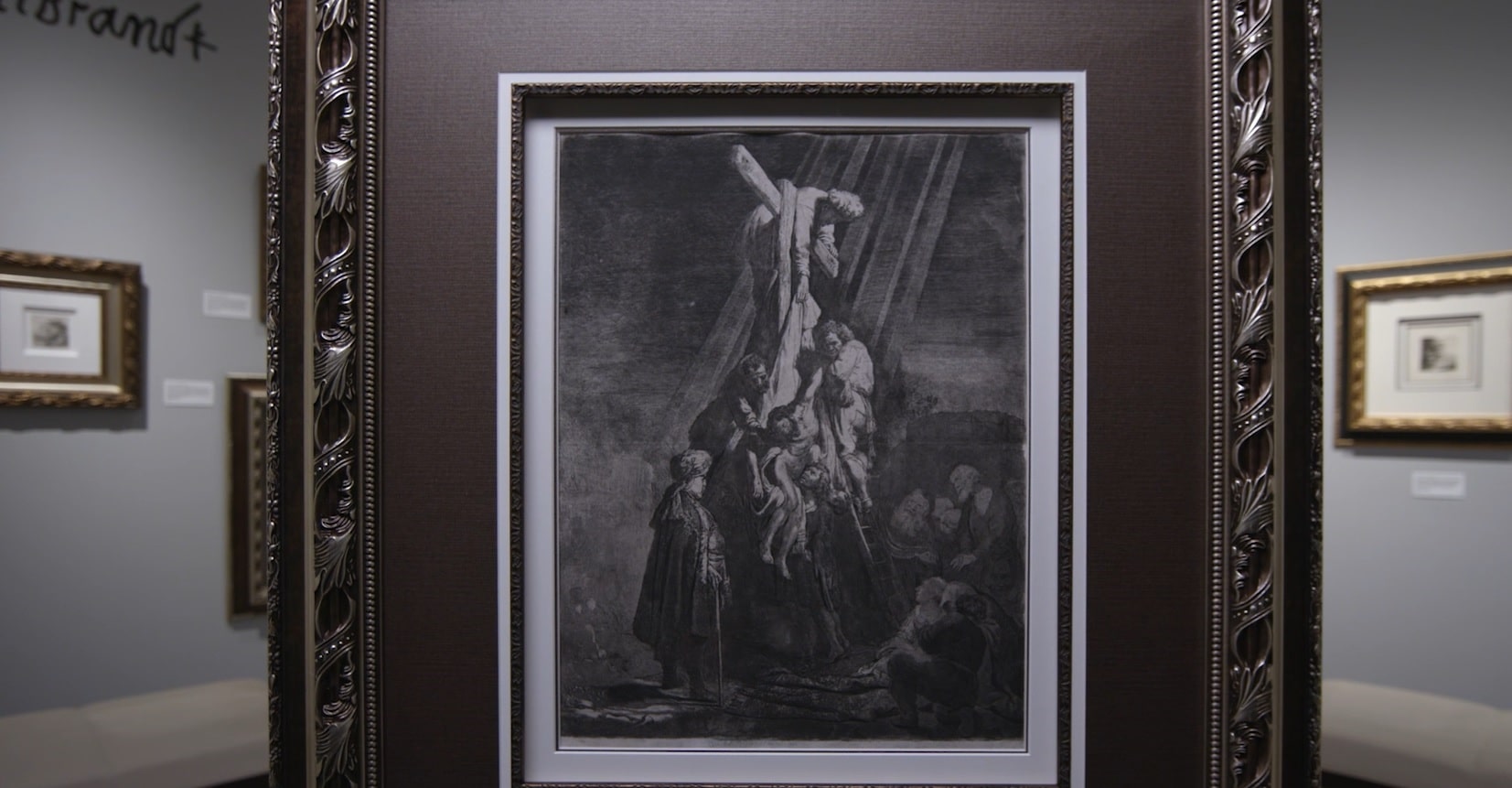

Etching, “The Descent From the Cross” (1633), Rembrandt Van Rijn

Ink applied to the cleaned plate settles into the etched lines and is then transferred to paper during the printing process, allowing multiple images to be created from a single plate.

Since most of the etching process is comparable to drawing on a sheet of paper, and the acid baths and printing could be handled by professionals, many artists found etching to be an easy and accessible printmaking process.

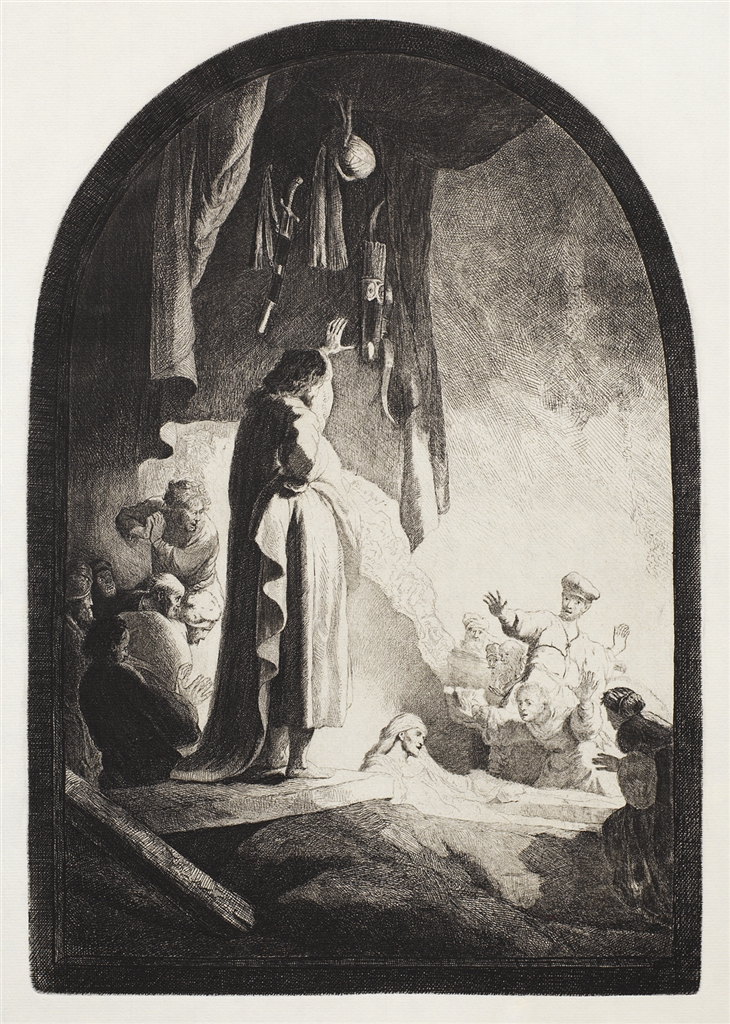

Etching, “The Raising of Lazarus: The Larger Plate” (c. 1630), Rembrandt Van Rijn

However, it did have its limits. If the acid bath was too weak, the lines would not show clearly, and stronger acids could cause lines to become irregular and print less finely.

REMBRANDT’S ETCHING INNOVATIONS

By the 17th century, more artists were working with etchings and many were attempting to refine the method, including Rembrandt.

However, what is extraordinary about Rembrandt’s printmaking is how he experimented with ink and paper to produce noticeable differences from one plate-pressing to another—a revolutionary technique that ultimately made a lasting impact on the art of etching.

Etching, “Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife” (1634), Rembrandt Van Rijn

Typically, when a plate was inked for an etching, the excess ink that had not settled into the etched lines was completely wiped from the plate. Rembrandt experimented with this process, allowing the ink to partially remain on the plates after each pressing. This allowed him to construct varying contrasts and tones, which changed with each printing. The artist used this tonality to create deep shadows that dramatically altered the atmosphere of a print.

Rembrandt also observed the different properties of various papers and inks and tested different combinations. He was particularly drawn to Japanese paper due to its yellowish color, which he found ideal for landscape prints.

From time to time, Rembrandt used different intaglio styles within his etchings—“intaglio” represents any printing or printmaking technique that involves adding ink to a plate with lines or indents added to it. One of those intaglio styles was drypoint, the process of drawing onto a plate by using a sharp needle. Drypoint pulls up pieces of the metal called “burr,” and the burr helps catch additional ink to produce a fuzzy texture within the print.

Many artists found the effect appealing, but the burr wears away quickly during the printing process, making it unsuitable for mass printings. However, Rembrandt found that, due to the smooth texture of Japanese paper, the drypoint elements of his prints were more distinguishable and did not wear away as quickly.

Etching, “Man in Cloak and Fur Cap Leaning Against a Bank” (c. 1630), Rembrandt Van Rijn

CREATIVE CHANGES DURING THE ETCHING PROCESS

Rembrandt not only experimented with the materials used to create his prints, but he also reworked his imagery. He was able to do this because of the nature of copper plates, which are comparatively soft and can be pounded or burnished so lines can be removed or added.

Rembrandt sometimes spent years working on a single plate, making prints from the plate between various changes. These changes—referred to as “states”—offer a rare glimpse into the artist’s creative process.

These states have been meticulously documented by Rembrandt scholars for centuries, in what are known as “catalogs raisonné” of his etchings. The most recent publication includes photographs of each state. These sources are referenced in the Park West descriptions for each etching and are the standard references used throughout the art world.

Etching, “Self-Portrait with Plumed Cap and Lowered Sabre” (1634), Rembrandt Van Rijn

The combination of the various states of Rembrandt’s prints, along with his distinctive printing techniques, created a sense of uniqueness in a method known for its mass production qualities. This, in turn, helped increase the popularity and collectability of Rembrandt’s etchings.

Collectors sought to acquire multiple examples of Rembrandt’s images in order to capture the variations between the different states. Through this, a record of Rembrandt’s creative process was captured and can be studied long into the future.

Rembrandt’s importance to the history of etching cannot be overstated. The over 300 etchings, engravings, and drypoints he created throughout his career helped influence generations of printmakers to come.

The Park West Museum in Southfield, Michigan has over 20 examples of Rembrandt’s remarkable etchings on display—including all of the etchings pictured in this article. For more information on visiting the museum, click here.

Park West Gallery Director David Gorman in the Park West Museum Rembrandt gallery.

The Rembrandt etching gallery at Park West Museum

To add a limited-edition masterpiece by Rembrandt van Rijn to your collection, register for our exciting online auctions or contact one of our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 during business hours or email sales@parkwestgallery.com for inquiries after hours.

RELATED LINKS: