The Strange History Behind Salvador Dalí’s “Divine Comedy”

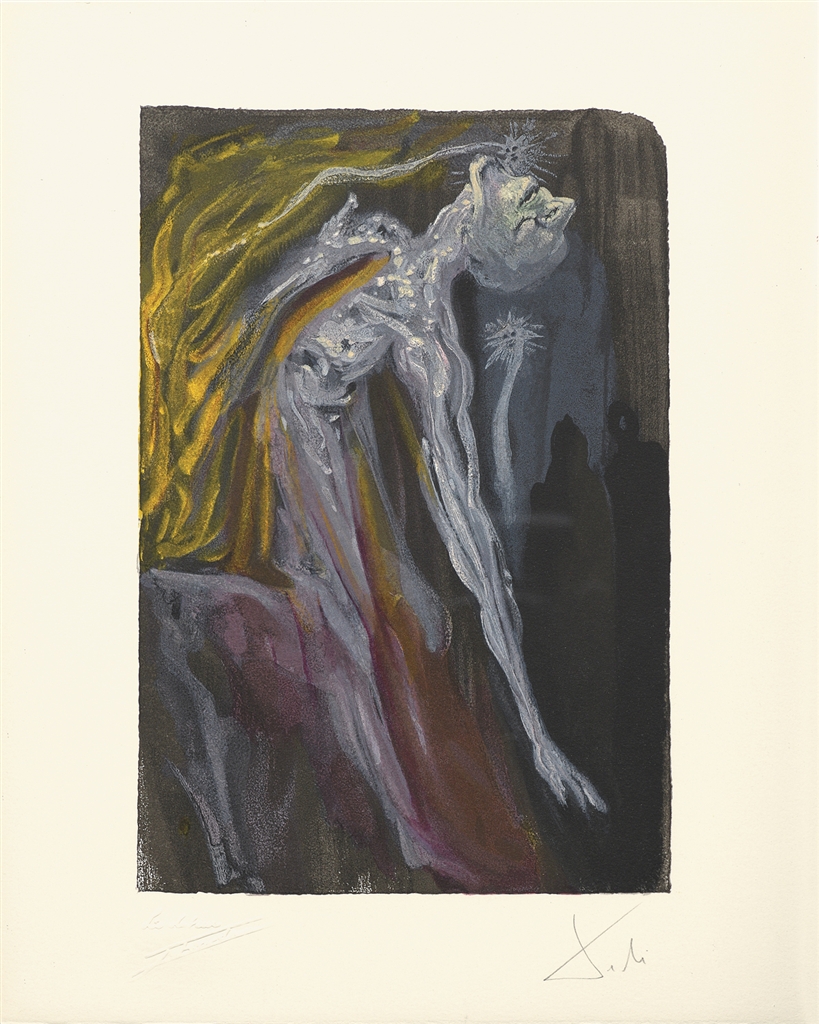

Detail from “The Grim Boatman’s Boat (La barque du nocher 1959-1963). From Dalí’s “Divine Comedy—Purgatory 2.”

Salvador Dalí was an unusual choice to illustrate Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy.”

Dante’s epic poem is considered one of Italy’s national treasures, a work embraced by both Italian cultural institutions and the Roman Catholic Church.

So it was decidedly odd when it was announced in 1950 that Dalí—a Spanish Surrealist who had rejected religion in his past—had been chosen to bring to life a work that was so distinctly Italian.

In the remarkable 2016 book, “Dalí—Illustrator,” art scholar Eduard Fornés offers a definitive history of how Dalí’s “Divine Comedy” came to be. Fornés knew Dalí personally and has written 20 books on the artist’s life and career.

In this excerpt from “Dalí—Illustrator,” Fornés explains why Italy chose Dalí to illustrate “The Divine Comedy,” why the Italian government eventually canceled the project, and why Dalí persisted with his illustrations, thanks largely to his affinity for Dante.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

From “Dalí—Illustrator” by Eduard Fornés:

The Divine Comedy: Italy vs. Dalí

In 1950, to celebrate the 700th anniversary of the birth of Dante, the Italian government commissioned Salvador Dalí to illustrate one of the most important works of Italian literature, Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

In November 1949, Pope Pius XII had granted Dalí a private audience and lo and behold! His Holiness had consented and, to everyone’s surprise, agreed to Dalí’s request to paint the Immaculate Conception. The painting Dalí finally created was to become one of his masterpieces, “The Madonna of Port Lligat.”

To many, this was considered not only an amazing gesture by a Pope, but also an audacious act considering that Dalí outrageously proclaimed himself “a Surrealist void of all moral values” during what many regarded as his “blasphemous” stay in Paris in 1929 with the Surrealist group presided over by André Breton.

The Italian government, jealous of the pontifical audience, did not want to be left behind, and the Libreria dello Stato Italiano [The National Library of Italy] signed a contract with Dalí for him to illustrate a work by one of the greatest symbols of the country, Dante Alighieri.

It was already incredible that “The Madonna of Port Lligat”—appearing with a transparent abdomen with the baby Jesus having a framed hole in his body containing some floating bread—was allowed in Roman Catholic Italian society at the time.

But to allow Dalí to be the one to illustrate “The Divine Comedy” was a completely different matter—according to some in government, it was a crime against the state.

The dispute reached the Italian Parliament and, rather than face a lawsuit from a left-wing member, the government decided to terminate the contract of Libreria dello Stato with Dalí, and the exhibition of his watercolors of “The Divine Comedy,” which should have taken place in Rome, was canceled.

Dalí, however, was enthralled by the work of Dante and was also already deeply immersed in the project. As a result, he decided to offer the project to the French publisher, Joseph Forêt.

In 1959, Forêt’s company, Editions d’art Les Heures Claires, the well-known publisher of limited-edition books illustrated with fine art, agreed to undertake the project and proceeded to purchase Dalí’s watercolors and all of the copyrights for the publication of “The Divine Comedy.”

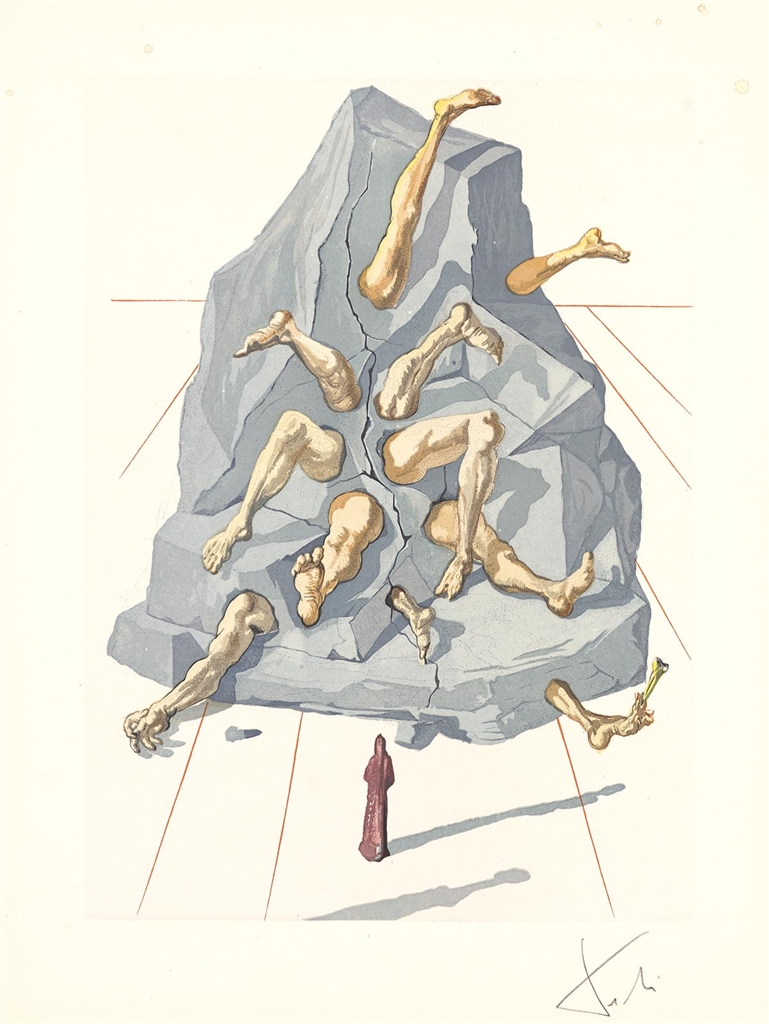

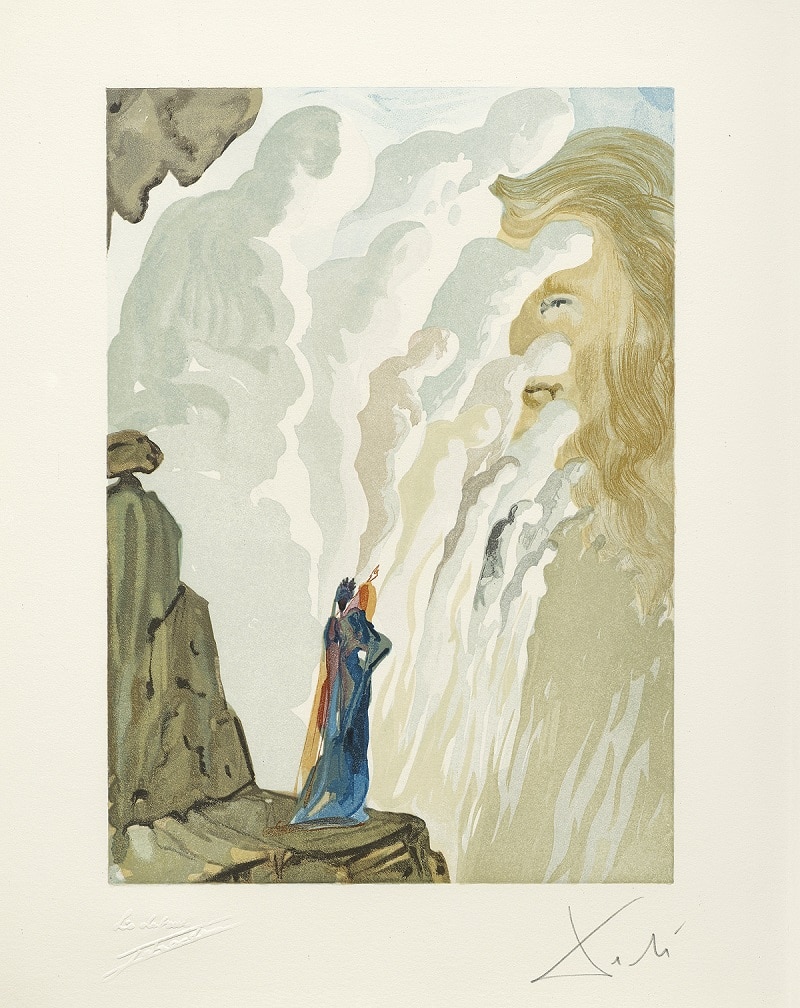

“The Beauty of the Sculpture” (La beaute des sculptures; 1951-64). From Dalí’s “Divine Comedy—Purgatory 12.”

Between 1951 and 1960, Dalí had painted 100 watercolors in preparation for the publication of “The Divine Comedy.” These watercolors explored the many myths and elements of this magnificent work of literature by the great Dante Alighieri.

The illustrations of “The Divine Comedy” are considered by many to be the most creative total body of work ever by Dalí. (In my opinion, there is no doubt.)

The illustrations represent the long journey that Dante took in 1300. In “The Divine Comedy,” it was on a Good Friday that he becomes lost in a dark wood and is attacked by three beasts: a panther, a lion, and a she-wolf.

His platonic love Beatrice sends [the Roman poet] Virgil to protect and guide Dante through the beyond—a trip through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise which Dante was to name “The Divine Comedy.”

Dante envisages Hell in nine circles, with steps descending to the very depths of the earth. On this journey to Hell, they find the damned in a series of terraced levels where they are punished according to how bad and perverse their sins are.

They all suffer terrible torments in scenes of terror, violence, and the presence of monstrous creatures. And, worst of all, that is where they must remain for all of eternity.

It is in the watercolors illustrating “The Divine Comedy” that the genius of Dalí is so overwhelmingly evident. For Dalí, it was instinctual for his creativity and talent to be completely unrestricted through his surreal imagination.

Nowhere is it more evident than in the visual power of these watercolors by Dalí, offering levels into Dante’s “Divine Comedy” that could never before be reached by words alone.

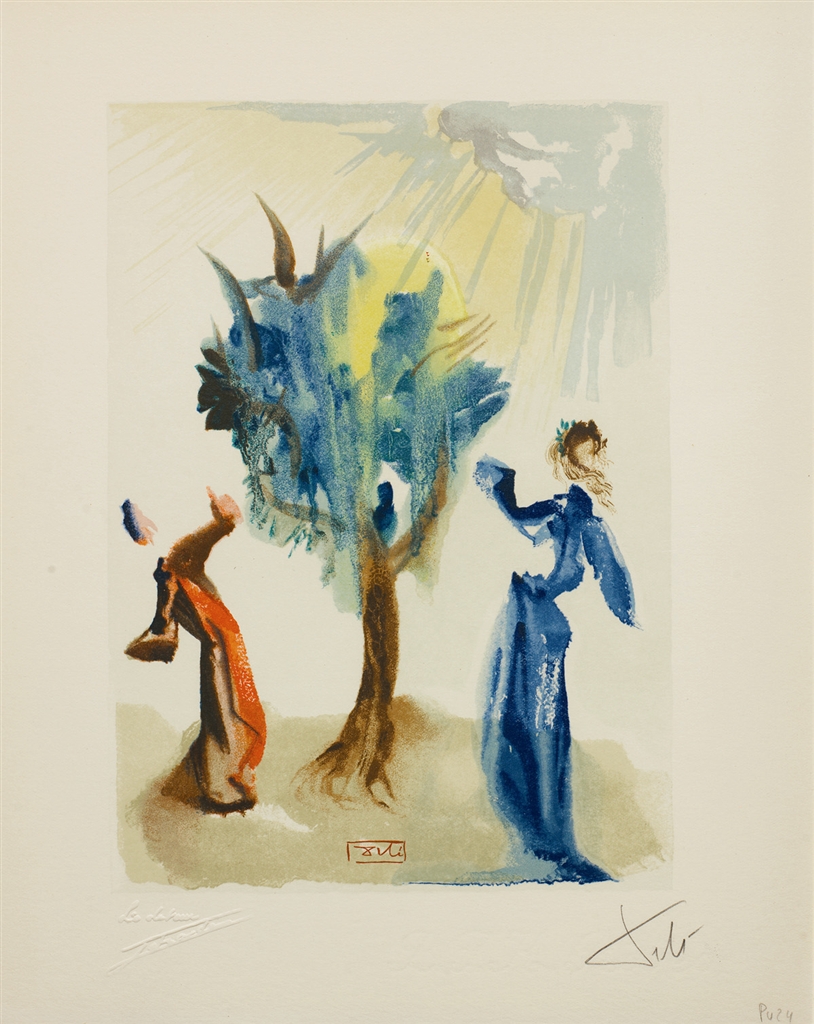

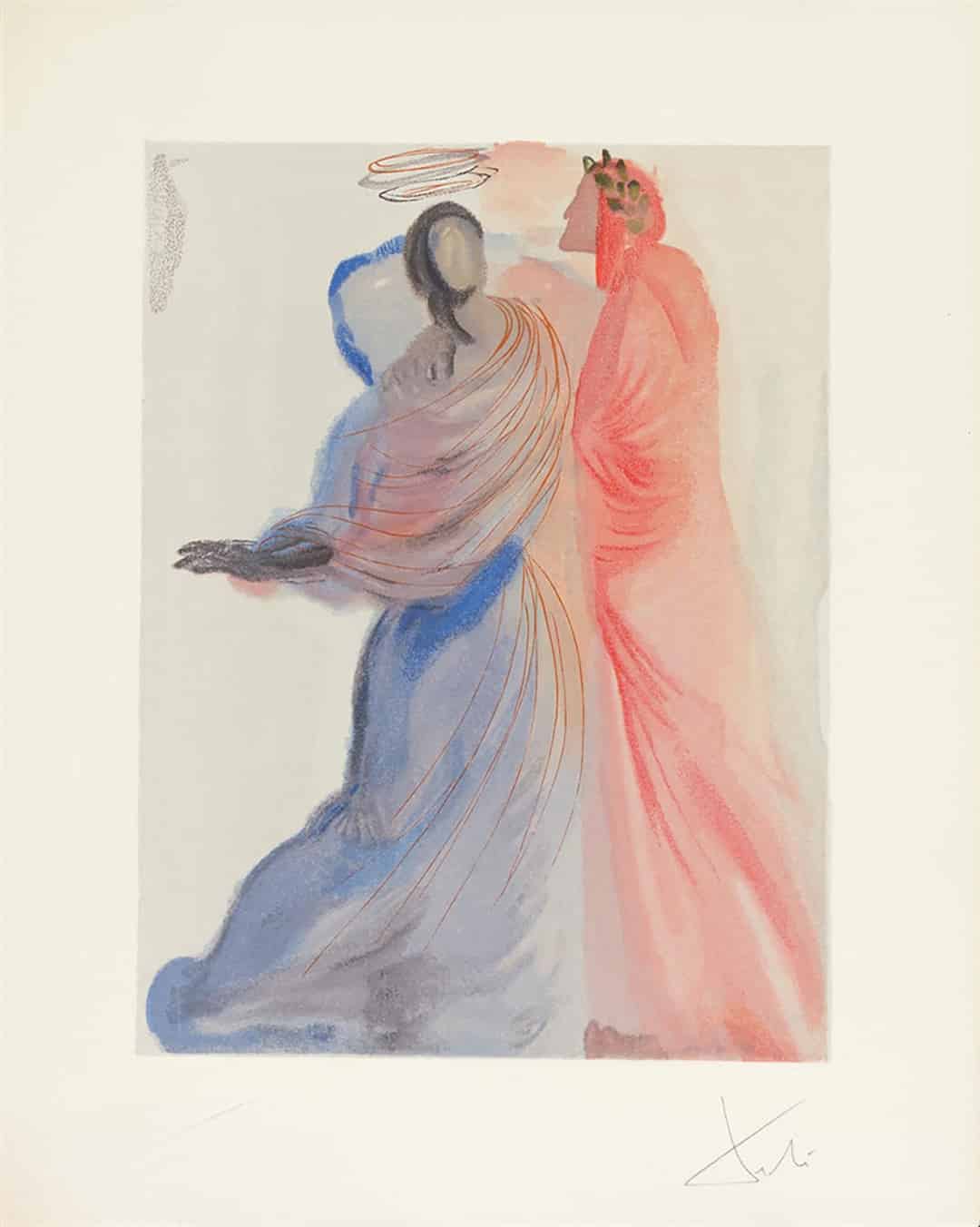

“Meeting of the Forces of Luxury” (Dante recouvre la vue; 1960). From Dalí’s “Divine Comedy—Paradise 26.”

In many respects, Dalí felt himself to be Dante. As Dante’s interpreter, Dalí felt obligated to follow the verses of “The Divine Comedy” and, through his watercolors, not only explain but also reconcile the writing of Dante.

By attempting to pictorially take the viewer through Dante’s series of incredibly complex situations, he set himself a difficult task, one almost impossible to achieve.

Being Dalí, it was impossible for him to refrain from applying his own interpretations—free and new. His fantasy flew and gave free rein to explore his own symbols and ghosts, so that, on many occasions, he unforgivably (to some) went off the track of the images as Dante described them in the text.

However, in many of the watercolors, Dalí was able to create powerful scenes, quite parallel to the fabulous poem, which were also striking as purely Dalí images by themselves.

“That blessed mirror now enjoyed alone his word within himself, and I too fed, tempering the sweet with bitter, on my own.” (1959-1963). From Dalí’s “Divine Comedy—Paradise 18.”

On May 19, 1960, an exhibition of the 100 watercolors illustrating the 14,000 verses of Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy” was presented, with Dalí in attendance, by Joseph Forêt and Les Heures Claires at the Museum Galliera in Paris.

Dalí had created 34 watercolors illustrating Inferno, 33 illustrating Purgatory, and 33 illustrating Paradise.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

This is where we’ll end the excerpt, however, it would take another three years until Dalí and Les Heures Claires were finally able to publish their first edition of “The Divine Comedy.”

If you’ve ever wanted to collect a work by a master like Dalí, now is the perfect time.

For more information on the art of Salvador Dalí, register for our exciting online auctions or contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or at sales@parkwestgallery.com after hours.

LEARN MORE ABOUT DALÍ’S “DIVINE COMEDY”:

- Collect Original Graphic Works by Salvador Dali in Our New Fall Sale

- Take an Inside Look at Salvador Dalí’s Latest Museum Exhibition

- Stairway to Heaven: Fascinating New Salvador Dalí Exhibition Begins U.S. Tour