The Fantastic History of Salvador Dalí’s Biblia Sacra

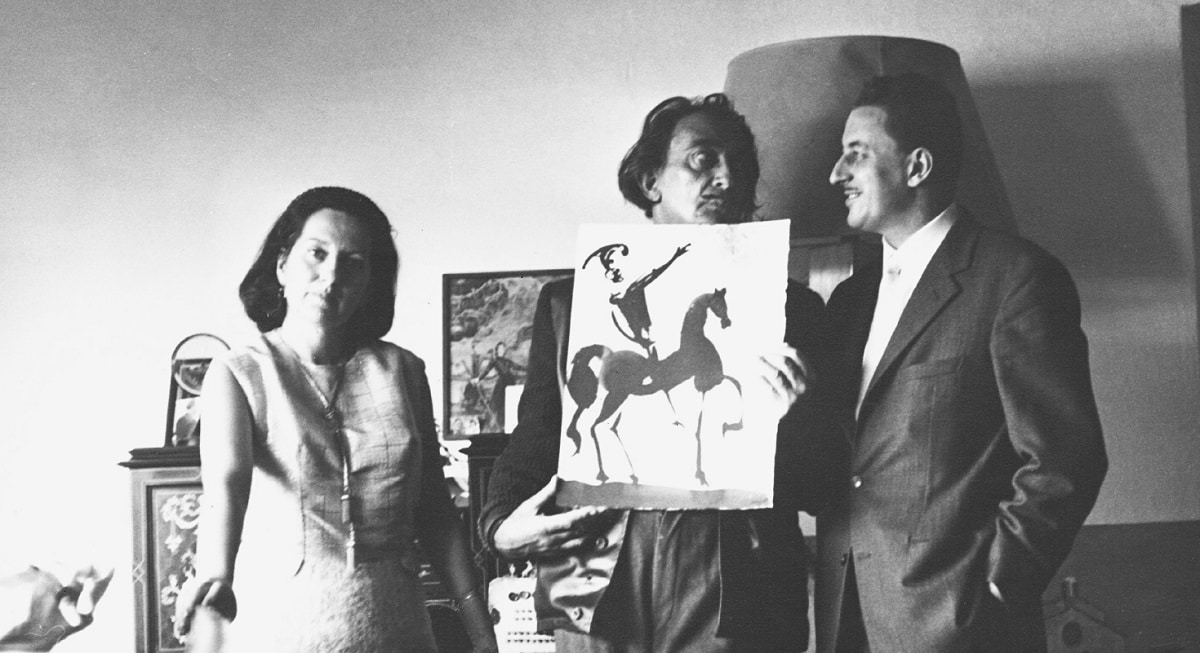

Salvador Dalí presenting the Albaretto family with one of his “Biblia Sacra” watercolors (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

Bernard Ewell is an internationally recognized expert in the art of Salvador Dalí. Here, Ewell presents a history of how one of Dalí’s most ambitious publishing projects came to be—the artist’s unrivaled illustrations for a special edition of the Bible known as the “Biblia Sacra.”

###

Some of the greatest intellectual and artistic creations through the ages have been the product of a genius working in solitude. Others are the result of the coming together of several people and an idea in a chemical reaction resulting in a totally new compound. That is the process that gives us the Biblia Sacra.

In 1963, Salvador Dalí—an internationally known artist and favorite of both the avant-garde art world and the media—turned his attention and energies to the endlessly rich subject matter offered by the Holy Bible (especially the Old Testament). The catalyst that permitted the artistic genius Dalí and The Book to create one hundred and five stunning and compelling images was Giuseppe Albaretto.

Italian Doctors Giuseppe and Mara Albaretto were vacationing with their young daughter Christiana in Llansa, just around the corner from the Dalí home at Cadaques on Spain’s Costa Brava in 1956, when they were taken to the artist’s home by art critic Rafael Santos Torroela. The visitors from Turin bought a drawing—the first of well over three hundred Dalí original artworks that now make up The Albaretto Collection.

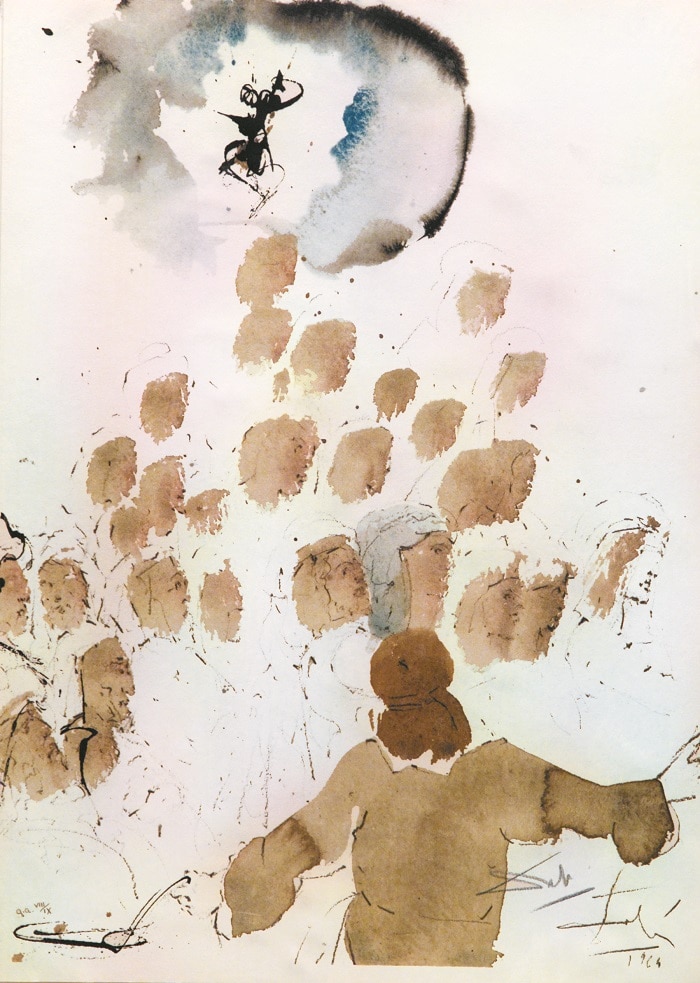

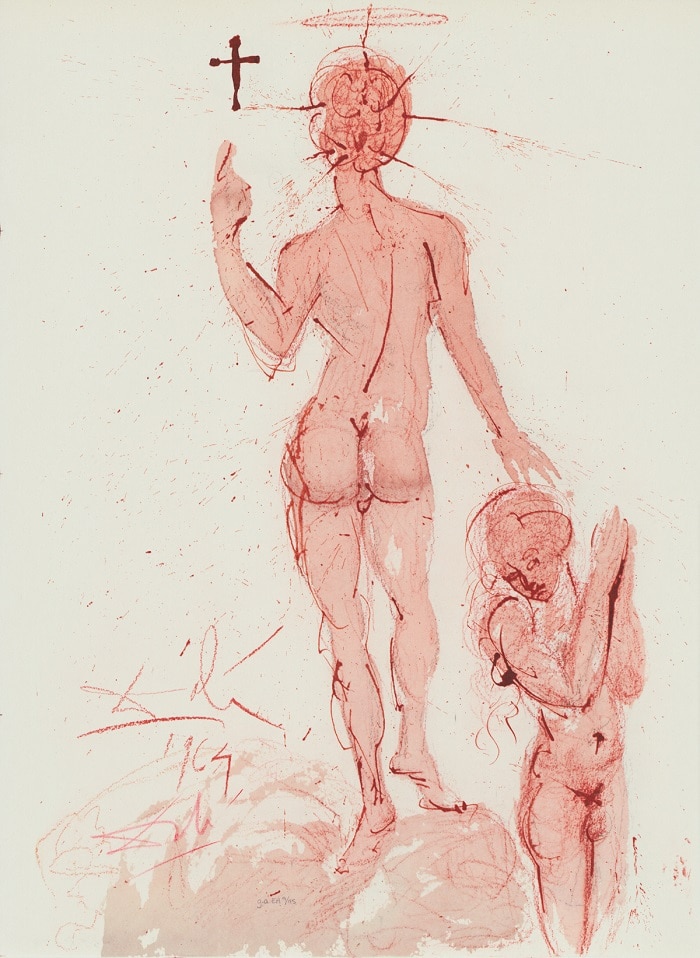

“Tu es Petrus… (You are Peter).” From “Biblia Sacra” by Salvador Dalí

Dalí, who usually had as much interest in children as did W. C. Fields, was uncharacteristically charmed by Christiana and invited the Italian visitors back. They were destined to become not only avid collectors who built the world’s largest collection of Dalí originals, but also the artist’s “Italian Family.” Christiana’s autograph book, with yearly entries of Dalí drawings, is today a delight and a treasure of the family. It was shown to me with great pride, as it is shared with all visitors to the family home in Turin who evince an interest in Dalí.

Christiana said, “For me, Dalí was a member of the family, someone that I had known forever, and who was part of my world. For example, I spent summers at the seaside in his village of Cadaques and it was like being home.” She went on to describe swimming and playing in the water with Dalí, enjoying the run of his home, and occupying herself in the studio while he painted.

The Albaretto’s wealth came from Mara’s olive oil producing family and Giuseppe’s position as a financial advisor to the Catholic Salesian Order—of which he had been a student until his family decided that as an only son, he had to “carry on” the family name.

Salvador Dalí with the Albarettos (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

Following his departure from the Salesians, who had provided his education and a desire to serve as a missionary, Giuseppe took a degree in dentistry and practiced for two years before returning to handle the finances of the monks. He was particularly involved in the Order’s educational publishing enterprises—experience that would assist him with the later publishing projects involving Dalí artworks.

When I was a guest in the Albaretto home after Giuseppe’s death, Mara (a physician) and Christiana told me many stories of his great faith and dedication to the Church. It was this that was responsible for the 1963 commission of Dalí’s illustrations for a new edition of The Bible with text in the Latin Vulgate language. This is the version that was prepared chiefly by St. Jerome at the end of the 4th century AD and used as the Authorized Version in liturgical services of the Roman Catholic Church.

“Tolle, tolle, crucifige eum (Away with him, away with him, crucify him).” From “Biblia Sacra” by Salvador Dalí

His wife and daughter told me that Giuseppe hoped the commission of one hundred mixed media paintings (there were eventually one hundred and five) would lead the artist to God. He believed that Dalí was completely dominated by his wife Gala, who was beyond redemption. In giving the assignment, Dr. Albaretto did everything he could to persuade his friend to meditate on the Catholic religion.

Giuseppe Albaretto believed that the commission would force Dalí to study the Bible, or at least read portions of it, especially the Old Testament. He later claimed the process “transformed” the artist, but few other observers were willing to agree with him.

Discussions about Dalí’s religious beliefs and relations to the Catholic Church have occupied many hours for many people in many locations over the years. Based more on conjecture than known facts, they have no more produced clear answers than have the comments of those who knew, to varying degrees, this incredibly complex man with a labyrinthine mind.

A survey of the extensive published writings of Dalí does little to answer the questions and provide a window into the artist’s relationship with his Creator.

“Nummularii de Templo eiecti (The Moneychangers Thrown out of the Temple).” From “Biblia Sacra” by Salvador Dalí

Carlton Lake, author of In Quest of Dalí, in 1969 quoted the artist as saying,

“During my adolescence, I was an atheist because my father was one. He was kind of anarchist. First I was interested in Freud and then in the sciences—biology and nuclear physics. The more I studied the sciences, the more I realized that everything religion tells us is true. Theoretically, that was fine. But I still lacked that grace which is faith. That is more difficult. I have the feeling it will come in a surer form, but I don’t know just when. It comes and it goes. It oscillates.”

The artist’s concurrent interest in science and religion is demonstrated by two paintings executed almost simultaneously in 1962-1963. The scientific work is “Galacidalacidesoxyribonucleicacid: Homage to Crick and Watson.” The thirty-three letter title refers to the discovery of the DNA molecule in 1953 (my cousin James Watson is so far the only member of our family to receive the Nobel Prize).

Even in this highly scientific work, there is a strong reference to God and the Resurrection as a symbol of hope. The purely religious painting is “Christ of Valles,” a centerpiece of the Albaretto Collection. “Galacidalacidesoxyribonucleicacid” is in the collection of the Salvador Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida, where I have appraised it.

Dalí had made a show of converting to Catholicism in the 1950s but rarely set foot inside a church after his marriage to Gala. This “conversion” followed his earlier alignment with the Surrealists and their 1931 call for a full bourgeois revolution to fight “for the day God would be swept from the surface of the world.” In Dalí’s opinion, people were hungry for the spiritual food that used to be supplied by Catholicism and could now only be provided by Surrealism or National Socialism.

“Gloria vultus Moysi (The Glory of Moses’ Face).” From “Biblia Sacra” by Salvador Dalí

Even so, religious imagery appeared in Dalí’s painting quite early. By 1943, Madonnas made an appearance. The first was a simple Madonna, but was followed that same year by “Madonna of the Birds with Two Angels” and in 1946 by “Temptation of St. Anthony.” Dalí’s 1946 Christmas design for the cover of Vogue, however, was purely secular.

The first really major painting based on a Christian theme was produced in 1949. Dalí transported the imagery of Piero della Francesca’s Brera altarpiece to the beachfront of his house at Port Lligat and transformed his wife Gala into the Madonna creating “The Madonna of Port Lligat.” Even though the painting is based on a Renaissance religious masterpiece, there is practically no religious iconography with only a tiny cross in the hand of the baby Jesus and no halos in evidence.

The most productive year for paintings with religious themes was 1952 when Dalí painted “Arithmosophic Cross,” “Nuclear Cross,” “Assumpta Corpuscularia,” “Madonna in Particles,” and “Angel of Port Lligat.” In 1954, he completed “Corpus Hypercubus” now owned by the Metropolitan Museum and on loan to The Salvador Dalí Museum. 1955 saw the creation of the stunning “Sacrament of the Last Supper” that captivates and moves visitors at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

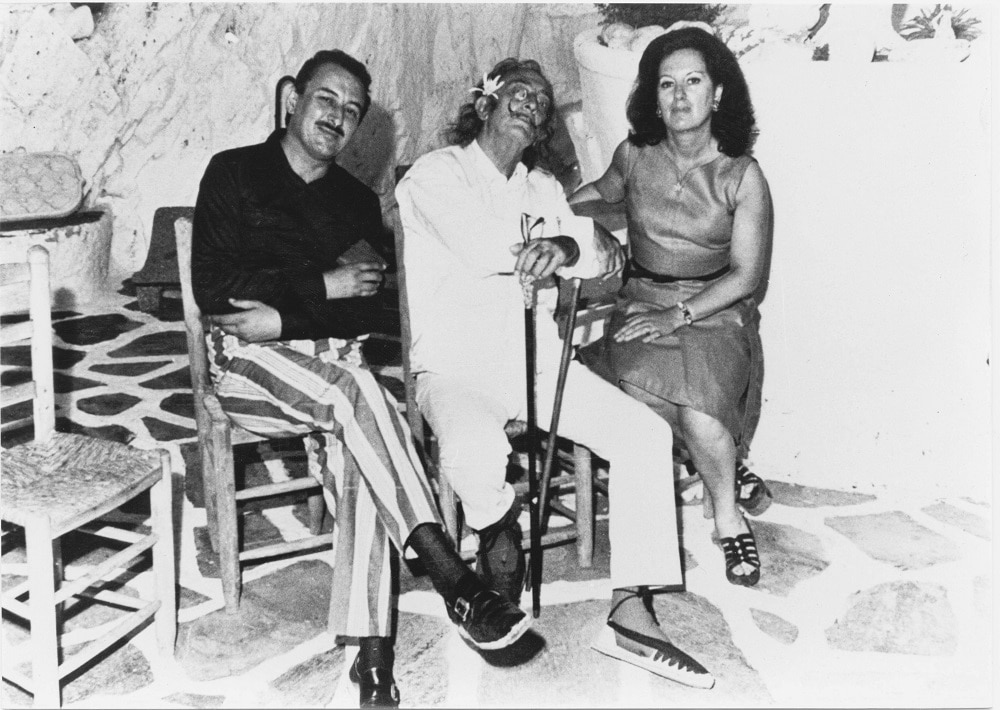

Dalí with the Albarettos (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

Continuing with religious subjects, Dalí painted “St. Helen of Port Lligat” (1956), “Ascension” (1958), and “Virgin of Guadeloupe” (1959). Also in 1959 Dalí had an audience with Pope John XXIII and then went on to paint “The Apocalypse” (1960), “The Ecumenical Council” (1960), and “Christ of Gala” (1978).

There are other, earlier Biblical references in Dalí paintings. For instance, in “The Old Age of William Tell” (1931), there is a reference to the Genesis story of Lot who escaped with his wife and daughters from Sodom and Gomorra. In several paintings, especially “The Lugubrious Game,” Dalí employs father and son images referring to The Prodigal Son—a topic of particular interest considering the artist was estranged from his authoritarian father most of his life.

“Et baptizatus est a Ioanne in (And He was baptized by John in the Jordan).” From “Biblia Sacra” by Salvador Dalí

In Salvador Dalí: A Mythology, Dawn Ades and Fiona Bradley write:

“Dalí’s construction of his own myth spread out to embrace myths drawn from the classical world and biblical history, which he both used with a directness unparalleled in other modern artists and recast to invest with meanings drawn from contemporary psychoanalysis…”

The paintings created by Salvador Dalí for the Biblia Sacra exhibit a wide variety of imagery—some Christian, but some clearly based on classical myths and texts. Other pieces exhibit the Dalínian use of Freudian concepts. Most demonstrate Dalí’s capacity for great leaps of imagination and some, I believe, reveal the artist’s capacity for thinking in a fourth dimension transcending time and space.

Men and women of art would say the Biblia Sacra illustrations demonstrate great creativity. Men and women of faith would say they demonstrate great divine collaboration. Either way, I find that each can also stand alone as an example of the artist’s work. As A. Reynolds Morse, who built the collection of The Salvador Dalí Museum, has written, “The fact remains, there are literally so many diverse expressions of Dalí’s talents that no one has yet been able to catalog them all, much less assess them artistically and aesthetically.”

The incredible range of creativity represented by the Biblia Sacra illustrations captivated me for three days in Turin when Mara Albaretto made the original mixed media paintings available for my examination. I was also permitted access to the artist’s authentications and documentation of the project.

Above all, I was impressed by the spontaneity of the paintings. Many were apparently begun using “bulletism.” This was a purely Dalínian invention. The artist, frequently referred to by Giuseppe Albaretto as “The Divine Master,” loaded an arquebus (antique firearm) with ink-filled capsules which were then fired at blank sheets of paper. Dalí worked with the resulting patterns in developing his images. Genius or Divine intervention?

“Asperges me hyssopo et mundabo (You will sprinkle me with hyssop and I will be cleansed).” From “Biblia Sacra” by Salvador Dalí

Each of the one hundred and five illustrations is tied to a biblical verse—and many are obvious in their references—but every one provides new ways of seeing the text. They celebrate The Bible as historical allegory and help us visualize the verses in new, less dogmatic interpretations.

The Biblia Sacra text is presented visually by Dalí with a modern view, enlivened by the comparisons with other civilizations, enriched by references to different literary genres, and imbued with a wholly appropriate timelessness. After all, our word “Bible” comes from the ancient Phoenician port of Biblos in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was the Phoenician traders who disseminated paper (papyrus from Egypt) throughout the Ancient World and gave the Greeks reason to use “biblos” (the source of paper) as their word for “book.”

Dr. Giuseppe Albaretto not only served as a catalyst to bring the great 20th-century artist Salvador Dalí together with the ancient text of The Bible, resulting in the illustrations of Biblia Sacra, but he also brought together the artworks and the Vulgate Latin text with the great Italian publishing house of Rizzoli.

Dalí with the Albaretto family at his house in Torino (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

In 1967, an edition of the Biblia Sacra was published by Rizzoli in Milan in five huge volumes bound in gold-tooled Florentine leather. Some, along with loose sheets, found their way into the collection of Roberto Mastella of Verona, Italy. All individual images in the Mastella Collection—bound and loose—were hand signed by Salvador Dalí and have been certified by me following my examination of each one.

Having examined the original paintings, as well as a large number of the printed illustrations, I am tremendously impressed by the fidelity of the prints. It is frequently difficult to tell they are not the original paintings. They are of a quality that would fool most viewers.

Truly, the coming together of the Albarettos, The Bible, and Dalí resulted in the creation of a set of images that represent far more than the sum of the parts. Even so, it is worth stating again that each image quite clearly can stand alone as an individual work of art by Salvador Dalí.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Bernard Ewell is an internationally recognized Dalí authority. He is an accredited Senior Appraiser who has provided professional services since 1972 and has specialized in the works of Salvador Dalí since 1980. He has appraised over 20,000 graphic works attributed to Dalí and examined over 800 unique, original drawings and paintings. In 1987, 1993, and 1998, he appraised the collection of the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. Mr. Ewell has been certified by the Albaretto Collection in Turin, Italy—the world’s largest collection of original artworks by the Spanish Master.

As a recognized expert in the field, Mr. Ewell has provided appraisals, court reports, and testimony for the Federal Trade Commission, the F.B.I., the I.R.S., the U.S. Attorneys of New York and Hawaii, the U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, the Attorneys General of New Mexico, Wisconsin, and Missouri, and numerous local law enforcement agencies and private attorneys. He also served as a consultant for the CBS News “60 Minutes” broadcast on the Dalí market and Money Magazine, Forbes Magazine, and numerous newspapers. Working with the Wisconsin Attorney General, he co-authored the Art Multiples Law, designed to serve as a model for other states.

Ewell personally authenticated Park West Gallery’s collection of Biblia Sacra lithographs in 1999.

If you’ve ever wanted to collect works by a master like Dalí, now is the perfect time. For more information on the art of Salvador Dalí, attend one of our exciting online auctions or contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or at sales@parkwestgallery.com after hours.