The Incredible Process of Bringing Salvador Dalí’s “Divine Comedy” to Life

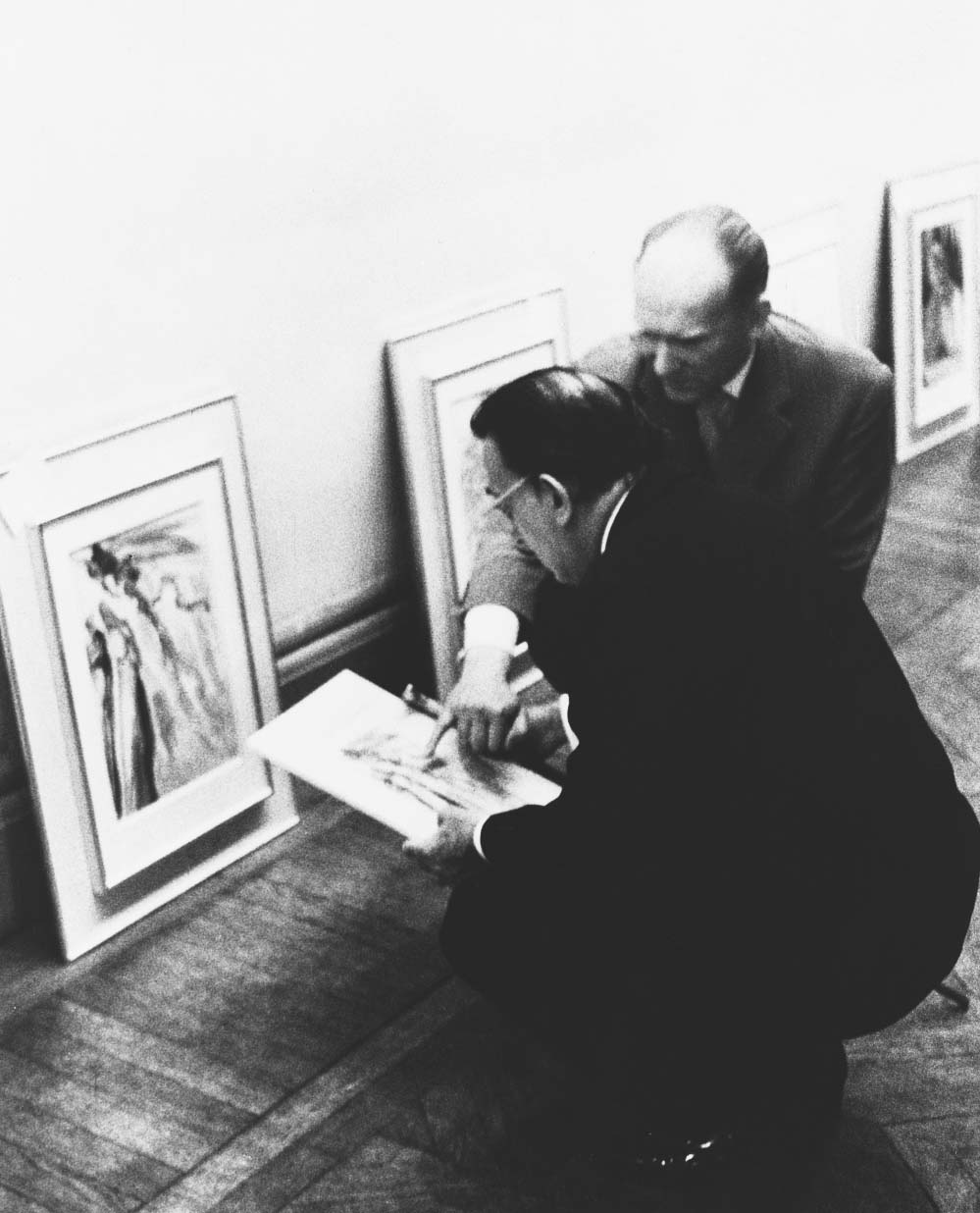

Joseph Forêt, Salvador Dalí, and the engraver, Raymond Jacquet, examining one of the engravings from “The Divine Comedy.” (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

In 1950, famed Surrealist Salvador Dalí began work on an ambitious project—he was going to illustrate Dante’s 14th-century epic poem about the afterlife, “The Divine Comedy.”

What he didn’t know at the time was that the “Divine Comedy” would occupy the next 14 years of his life.

Previously, we recounted the history of how the project first started, beginning with a commission from the National Library of Italy (which would eventually be rescinded), and left off in 1960, when Dalí had finally finished his initial 100 watercolors for “The Divine Comedy.”

However, the next step in Dalí’s project was surprisingly difficult. Dalí would have to team up with the French publisher Joseph Forêt and his company, Les Heures Claires, to turn the 100 watercolors into a series of engravings.

This was a monumental undertaking, requiring almost 56 months of continuous work.

Noted Dalí expert Eduard Fornés assembled a definitive history of Dalí’s “Divine Comedy” in his 2016 book, “Dalí—Illustrator.”

In this excerpt, Fornés explains the enormous complexity involved in engraving Dalí’s “Divine Comedy” and how Dalí was personally involved in every step of the process.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

From “Dalí—Illustrator” by Eduard Fornés:

Dalí’s Divine Comedy: From Paper to Wood

In 1959, Jean Estrade, the artistic director of Les Heures Claires of Paris, commissioned Raymond Jacquet to be the engraver of the blocks used to create the 100 wood engravings of Dalí’s “Divine Comedy.”

Raymond Jacquet—working in collaboration with and under the supervision of Dalí himself for a period of four years (1959-1963)—engraved the blocks that were used in the printing.

Although referred to as “wood engravings,” rather than working on wood, Jacquet worked on resin blocks, which were harder and were able to retain a more consistent quality when printed.

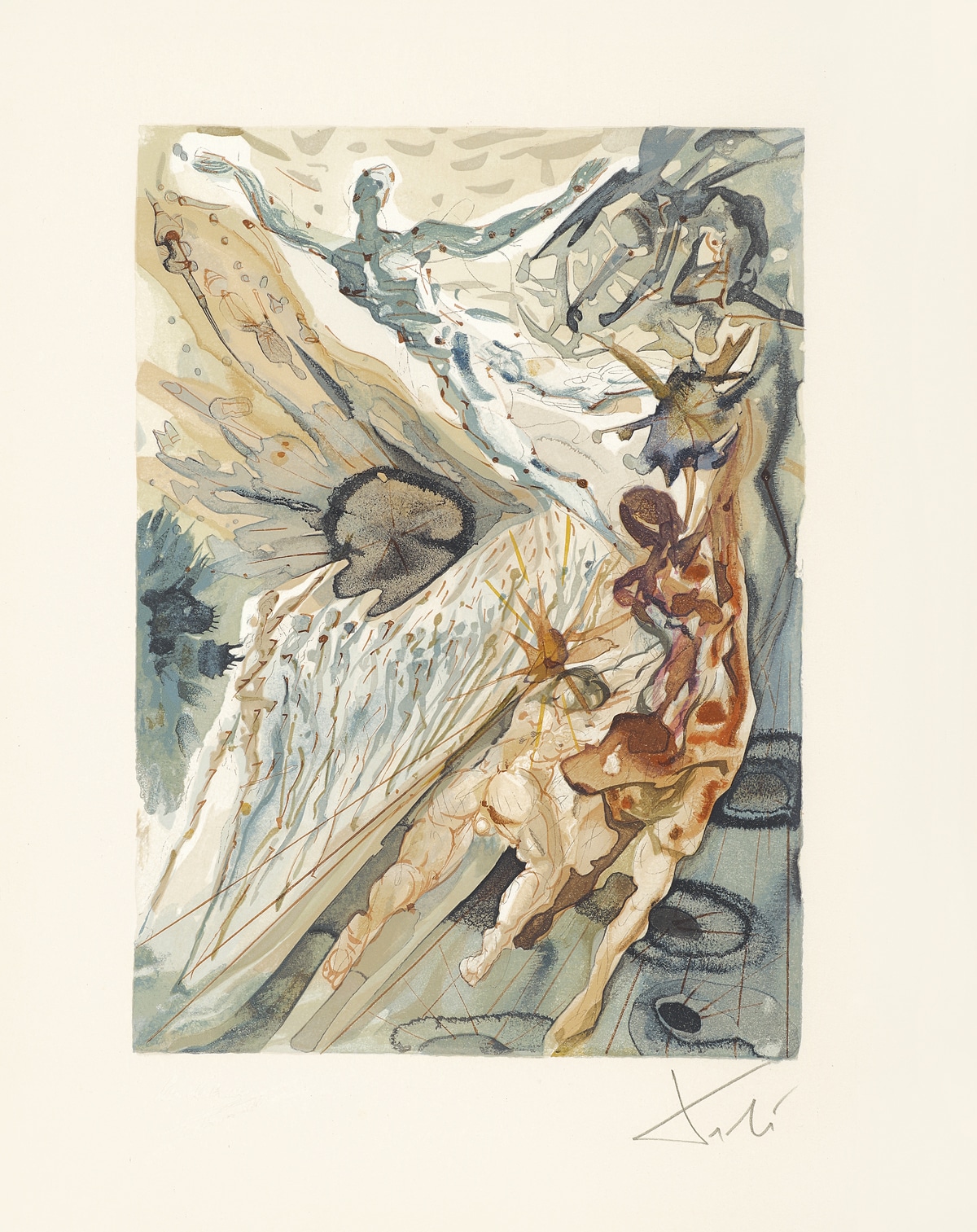

In viewing what are known as the “decompositions”—the single color proofs—of the wood engravings, one can see more than 30 colors used for just one of the completed engravings.

The decompositions are rare in the oeuvre of “The Divine Comedy” since relatively very few were ever printed. Decompositions of specific images have been included in some of the complete sets of “The Divine Comedy.”

Raymond Jacquet utilized the technique of engraving the same block to print different colors. By engraving again on the same block, it could never be used again to print the previous color.

As a result, “The Divine Comedy” could never be reprinted as the blocks were permanently changed during the process. In total, Jacquet would end up engraving the resin blocks for printing more than 3,500 times, an arduous job which took four years with Dalí’s collaboration and supervision.

Salvador Dalí and Jean Estrade examine wood engraving proofs for “The Divine Comedy” during preparations for the exhibition of Dalí’s “Divine Comedy” watercolors at the Museum Galliera, Paris (May 19, 1960). (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

The ability of the blocks to print engravings was eradicated at the time of printing by engraving again and again on the same block after the colors were printed.

In hindsight, it can be seen how clever and important this decision was, since, as a result, un-authorized examples or forgeries of the wood engravings can never successfully be made.

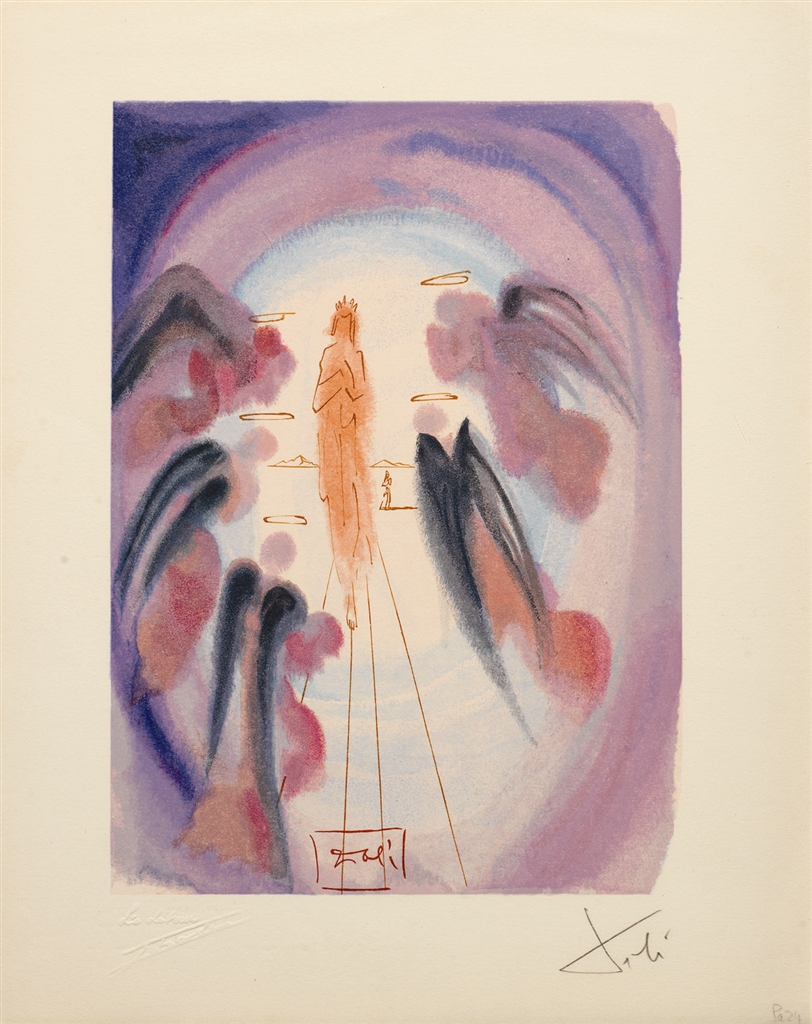

“Meeting of the Two Groups of Lechers (Recontre de deux troupes de luxurieux).” From Dalí’s “Divine Comedy – Purgatory 26″

The project was carried out under the supervision of Jean Estrade working closely together with Salvador Dalí, who himself approved each of the wood engravings with a “bon à tirer” (good to pull) proof.

Both Estrade and Jacquet interacted closely with Dalí, who spent a great deal of time in Paris during these four years. The artist approved and worked on the drawings for each of the engravings and personally approved, through continuous modification, each of the colors used.

Salvador Dalí, Jean Estrade, and Joseph Forêt review wood engraving proofs for “The Divine Comedy” at the Museum Galliera, Paris (May 19, 1960). (Photo credit: Eduard Fornés)

The process for the execution of these 3,500 resin blocks meant complete dedication on the part of the engraver. Jacquet’s technical and artistic talent achieved a quality that has rarely been equaled and arguably never surpassed.

[…]

“The Divine Comedy” of Salvador Dalí is unique in the world and in the history of modern art, and can comfortably and properly be referred to as “spectacular.”

For more information on the art of Salvador Dalí, contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or at sales@parkwestgallery.com after hours.

LEARN MORE ABOUT DALÍ’S “DIVINE COMEDY”:

- Collect Original Graphic Works by Salvador Dali in Our New Fall Sale

- Take an Inside Look at Salvador Dalí’s Latest Museum Exhibition

- Stairway to Heaven: Fascinating New Salvador Dalí Exhibition Begins U.S. Tour