Discerning Eyes, Abstract Musings: Artist Tim Yanke Comes of Age

Tim Yanke

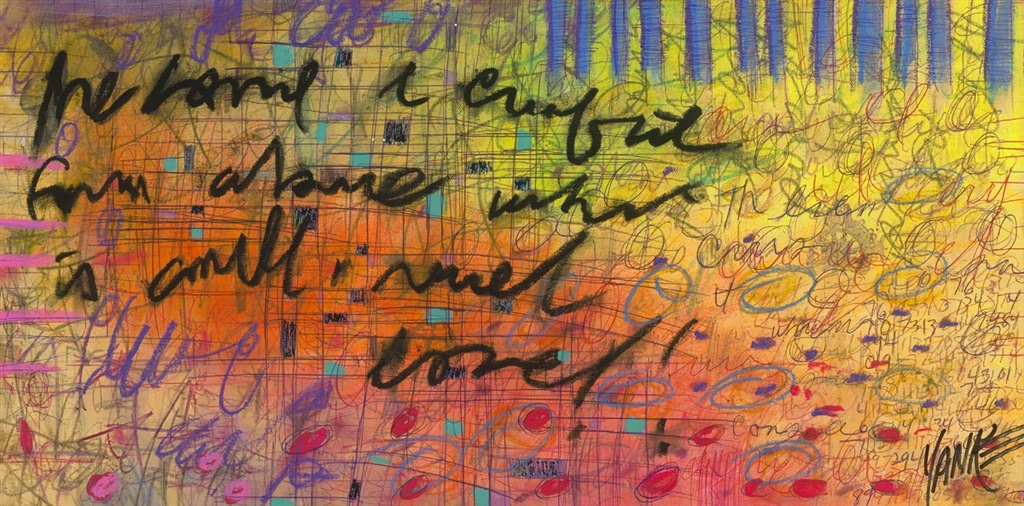

In 2018, the prestigious Monthaven Arts & Cultural Center in Tennessee opened an exciting new exhibition on the abstract works of artist Tim Yanke. Titled “Abstract Musings,” the exhibition showcased Yanke’s vibrant, lyrical paintings and firmly established Yanke as one of the most accomplished abstract artists of his generation.

Here’s a short history of Yanke’s career—composed for the opening of “Abstract Musings”—that nicely encompasses the origins of his interest in art and his remarkable personal journey as an artist.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

The artistic coming-of-age of painter Tim Yanke is, like many coming-of-age stories, a tale of fits and starts and fertile spurts, interspersed, naturally, with periods of unintentional paralysis. But, Yanke’s determination, discipline and resilience, accompanied by a powerful voice of encouragement, the shadow of personal tragedies, and cherished memories of family vacations traversing the terrain of the endless American west, have kept his creative trajectory moving steadily forward.

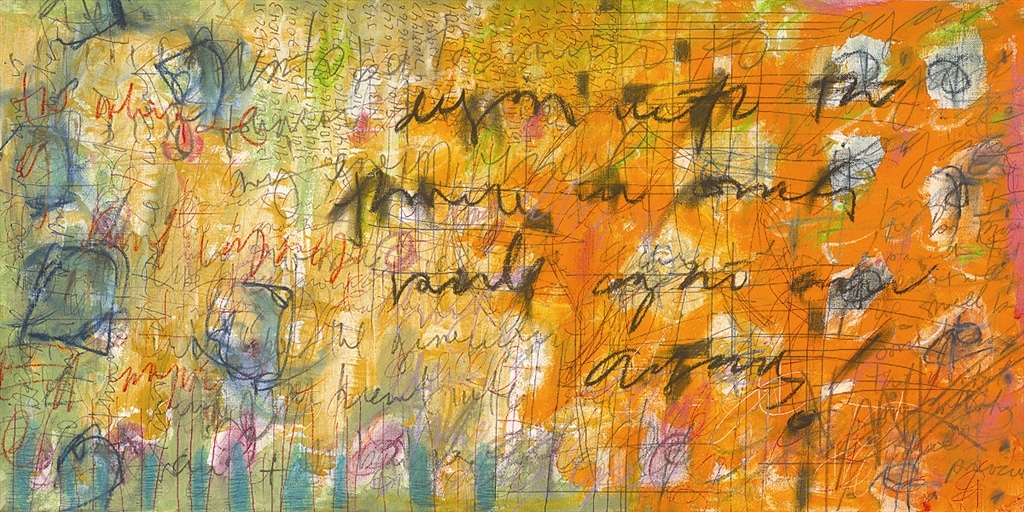

“Pine Horizon (031017.01)”

It was two years into the youth-led, British-born, cultural revolution of the Swinging Sixties when Yanke entered the world in Detroit, Michigan. In 1962, a seminal year in American history, gasoline was a mere 28 cents a gallon in the U.S., astronaut John H. Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth; student James Meredith was escorted onto the University of Mississippi campus by Federal marshals as the school’s first black enrollee; the Cuban missile crisis poised the world for war; legendary actress Marilyn Monroe died of a suspected suicide; Bentonville, Arkansas became the site of the first Wal-Mart store; the first of 26 iconic James Bond films was released, and American artist, sculptor, fashion illustrator, publisher and printmaker Andy Warhol first exhibited his now-famous paintings, Campbell’s Soup Cans (there were 32 of them!) while singer Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” had the entire country on its feet doing the tune’s namesake dance.

Yanke says he feels fortunate to have been born—the youngest of six—into a house full of siblings. The city where they lived had been founded by a French nobleman explorer in 1701, more than 200 years before it would become the epicenter for American automobile manufacturing. While Detroit was also where the blending of the soul and pop music genres would emerge as the world-famous “Motown Sound” in the late ‘50s and ‘60s, the city’s fortunes were already declining by the time Yanke arrived.

Amidst the changes to the car industry, the flight to the suburbs, and the surprising hostilities which African-Americans experienced in the “Motor City,” Detroit was a place marred by unrest, yet decidedly enlivened by its bright spots of musical genius. It was in this environment that Yanke grew up, highly attuned to the fact that momentous stories, ranging from heart wrenching to spiritually uplifting, could arise from almost any quarter.

“Nights and Weekends”

With his artistic sensibility and discerning eyes, Yanke began to encounter stories at every turn, snippets of which would later serve as the foundation for his visual art. Sundays were particularly significant for the young artist, as they were days of dedicated family camaraderie, providing the kind of nostalgic reverie that grows to mythic proportions in one’s memory.

He lived in the same suburban house for the entire span of his childhood, recalling it as an indulgent atmosphere where the boisterous rabble rousing of growing kids was affectionately tolerated. Yanke says his affable family was widely known, describing the clan’s collective bonhomie as legendary. He grins broadly in remembrance of those years, imagining them as warm, comforting hues, the very same ones which now blend together so seamlessly in his paintings.

With regard to any specific catalyst which might have engendered his career, Yanke doesn’t subscribe to the notion of fate alone. He humbly credits the origins of his accomplishments to the unwavering support he received from others, characterizing their bolstering as a positive accumulation of “little things.”

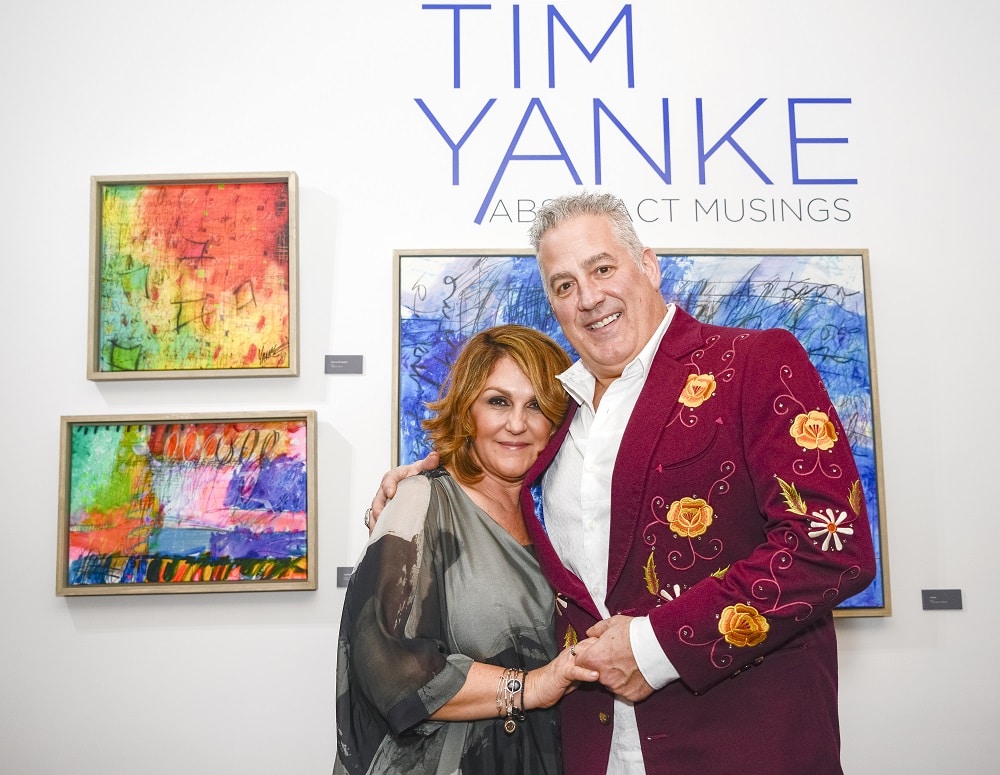

“Tim Yanke: Abstract Musings” exhibition at the Monthaven Arts & Cultural Center

He especially recalls a Sunday afternoon when his dad, while glancing at an early example of his work, made this seemingly offhand statement: “You have a great imagination!” The praise in that sentence carried inordinate weight for Yanke, fostering his ambition and kickstarting his promise as a burgeoning artist. At the time, he says, he thought, “Well, then it must be so.”

His father’s admiration, writ large upon his son’s psyche, still surfaces in Yanke’s subconscious today, materializing at watershed moments in his career as a flashing beacon of reassurance. Those kind words, spoken long ago to an eager young boy, continue to supply motivation, as Yanke refines his talent, still exploring, experimenting, and stretching in new directions. His artistic inclination, ignited at the family kitchen table all those decades ago, is his secret talisman. It is with him, always, wherever he goes.

As a child, Yanke’s imagination was kindled by the view from the backseat window of his dad’s iceberg blue Cadillac, its real-time moving picture unfolding with every ride. The Yanke family spent lots of time exploring the American Southwest from Texas to New Mexico to Wyoming and Arizona.

“Beyond Was All Around Me”

Even as a kid, Yanke realized that the landscape there was refreshingly different from that of Detroit—so open, so vast and so quiet in comparison. The familiarity of the terrain along Highway 40 became embedded in the mind’s eye of the young artist, its nutmeg and cinnamon shades figuring prominently in his work years later.

In 1976, Yanke’s older sister—then a student at Northern Arizona University— passed away during a drive back home to Michigan. This traumatic event would weigh on the Yanke family for years to come; a void which remained constant, sometimes cresting, sometimes subsiding a bit. Her sudden death defined Yanke’s life between the good ole days when she was still with them, and the days which came afterwards.

As one of Yanke’s brothers recently succumbed to cancer just this fall, he still struggles with this emotionally complex subject, though he tries to believe we’re rarely given things we can’t handle.

In 1982, Yanke himself set off for the American flatlands where he would nurture his infatuation with the fine art of design as a student at the University of North Texas. From the album covers scattered everywhere in his family’s basement to the screen print on his beloved Grateful Dead shirt—the art of objects had long captivated him.

“Buffalo”

He saw illustrators, architects, and designers as fascinating individuals who not only thought “outside the box”—they were “the creators of the boxes,” and he was desperately determined to be one of those.

Graduating four years later with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in advertising and graphic arts, Yanke began carving out a position in the world of corporate advertising. Young, ambitious, and admittedly starry-eyed, the aspiring designer set off to translate his idea of success into tangible reality. While he had demonstrated a passion and proficiency for painting during his days at North Texas, he returned to his home state to become not a painter, but a graphic designer at Ameritech (later known as AT&T).

For nearly 18 years, he forged ahead in the corporate arena, month after month filled with impending deadlines, myriad meetings, and never-ending nights at the office. Yet, it was also a time filled with the warmth and comfort of a meaningful relationship. He eventually married Nicky, his enduring sweetheart, in 1989, having caught a glimpse of what was “meant to be” a decade earlier in their high school hallway.

It goes without saying that his marriage proposal was unlike any other, appropriately fashioned, and brimming with artistic flair. He cast the words, “Nicky, Marry Me,” in metal and illuminated them in a glow of brilliant neon. Of course, she said “yes.”

Nicky and Tim Yanke

Years later, that same sign now graces the walls of the studio where Yanke happily spends his days, brush in hand, music blasting, whether he is listening to Phish, Stevie Wonder, the Charlie Daniels Band, the Disco Biscuits or the Ozark Mountain Daredevils. Other musical influences on Yanke’s wildly diverse “life playlist” include: the Dave Matthews Band, the Allman Brothers, the three “J’s—as in Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell and Janice Joplin—, the Rolling Stones, Johnny Cash, Duke Ellington, STS9, Railroad Earth, String Cheese and absolutely everything Motown.

As Yanke’s family expanded (son Roman was born in 1993, followed by son, Angelo, three years later), so did his creative aspirations. Unfortunately, his profession became more and more demanding, with its grind of unending tedium wearing him down. Six designs a day slowly increased to 10, which eventually rose to a required 18.

Meanwhile, in his estimation, the greater creative output compromised quality, leaving Yanke with an overwhelming sense of discontent. After devoting more than two decades of his career to the graphic design field, the artist’s energy and enthusiasm were waning. Frustrated, he began to dream of the freedom to produce the art that he truly wanted to make.

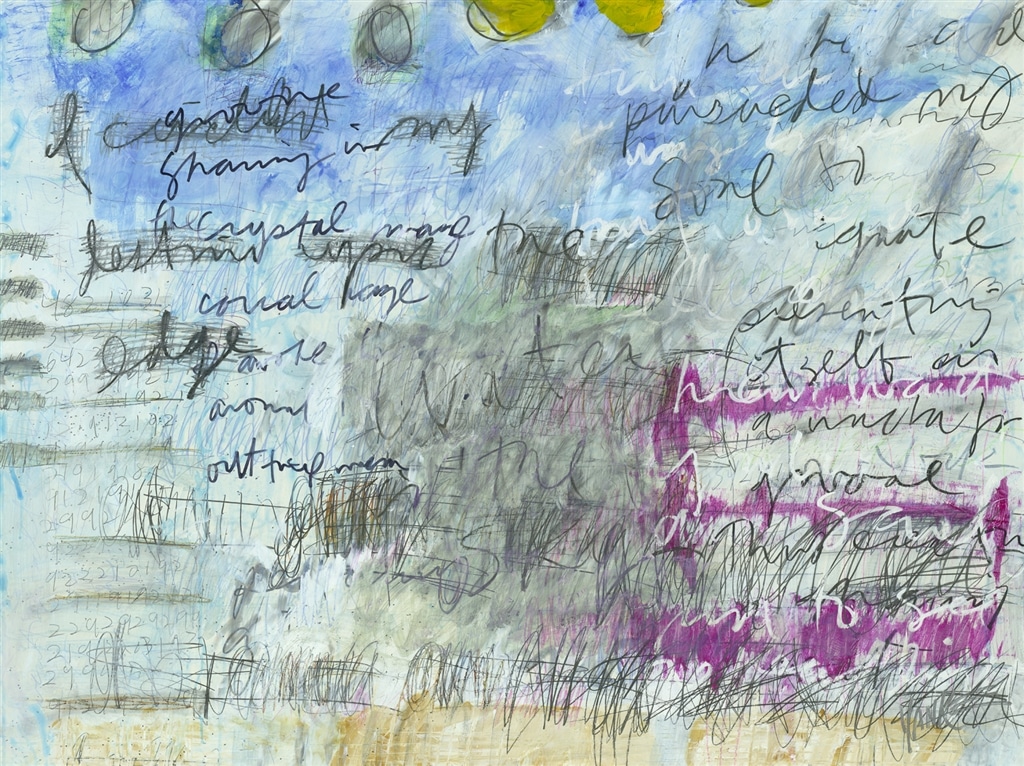

“Set One”

So, he began envisioning himself embarking on a different journey. A kind of storyteller by trade, he was eager to cast aside the corporate “stories” he’d been telling for so long in order to stake his claim as a working visual artist: simply put, he would paint, yes, paint. Every day. Inspired, he began working in his now-familiar, stream-of-consciousness style, hoping to rise to every artist’s standard call to action: “Paint something that no one has ever seen before.”

Naturally, Yanke’s fresh beginning, like any adventure, was imbued with the triumphs and struggles typical of such endeavors. In his early days as a fine artist, each illuminating breakthrough in his work seemed to be accompanied by the opposite reaction—an equally crushing disappointment. While local art fairs enriched Yanke’s reputation, they also positioned him as a target for jarring, unexpected criticism. Like thousands of artists before him, he just shrugged, put his head down and carried on.

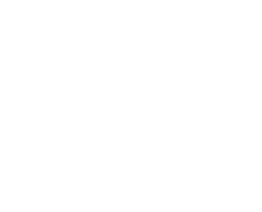

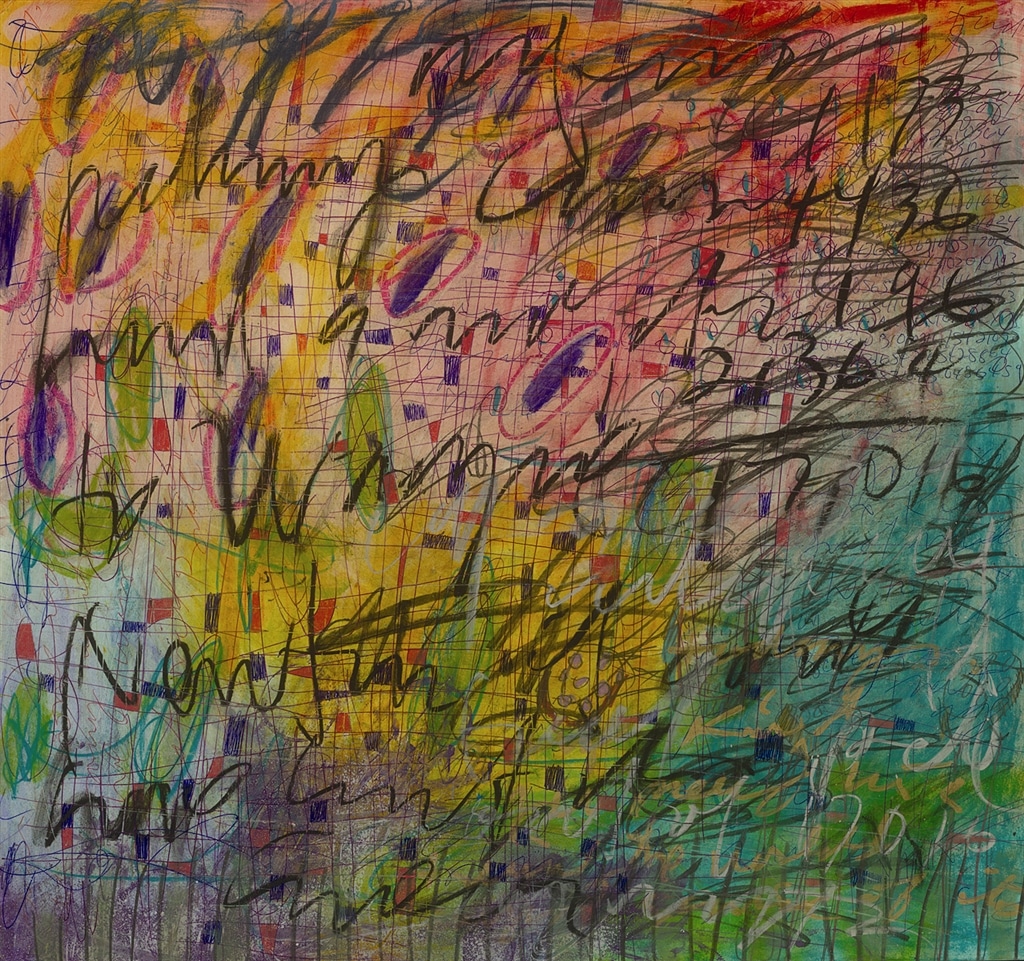

Harnessing the unbridled influence of the New York School and the Art Students League of New York—Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, and Robert Motherwell—Yanke’s artworks were defined by the gesture and spirit of the Abstract Expressionist movement. The farther he strayed outside the lines with his abstract body of work, the more frequently he heard the uninformed, yet well-worn refrain, “Oh, my kid could do that.” In truth, however, no kid could.

Yanke’s abstract works on display at the Monthaven Arts Center.

Yanke’s artwork wasn’t born of inexperience or idealism; it arises from depths of maturity layered with years’ worth of trial-and-error. One of his most endearing qualities is the way in which he regularly ruminates about art as “a profession,” and the inherent responsibility he feels in his role as an artistic “narrator.”

His reflections manifest themselves both in what we see within his work, and in what he leaves out, giving the viewer room to draw their own suppositions; arrive at their own conclusions. He thinks some stories appear more beguiling (he doesn’t reveal which those might be) when obscured, while others seem more striking to the viewer when they find meaning on their own.

The composition of his abstract works is drawn primarily from the music he has playing whenever he is in front of a canvas with a brush or other tool in hand. He doesn’t stop to read emails and almost always lets the ringing phone go unanswered.

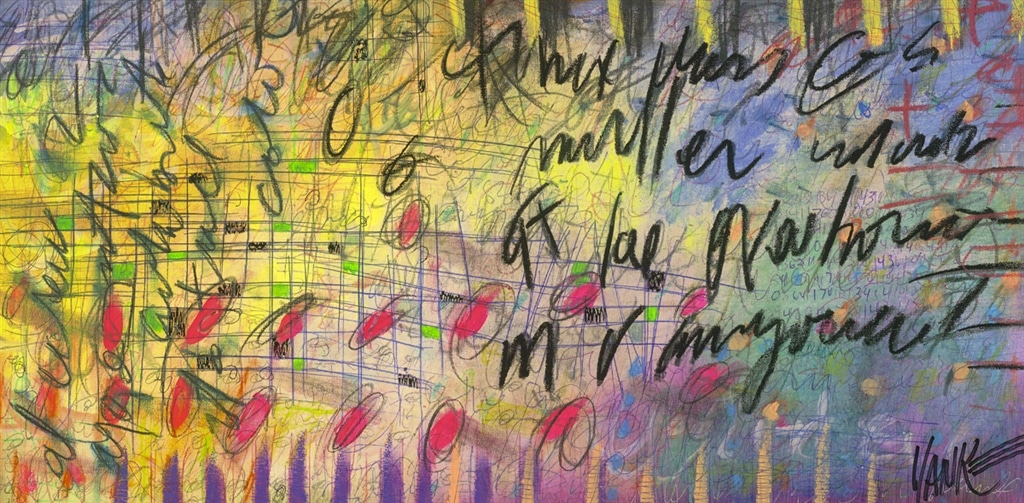

He says his extremely broad musical tastes are derived from two parents who adored music of all kinds, and that he thoroughly enjoys incorporating both song lyrics and titles into his work in a “loose, illegible scripty” manner. Most viewers can’t actually decipher it, which he prefers, because the veil of mystery makes for a deeper sense of intrigue and curiosity with the text/lyrics serving as a natural, organic design element.

“Tea Leaf”

In 1999, Yanke was afforded a break beyond regional recognition when he became affiliated with Park West Gallery in Southfield, Michigan. Within the company’s immense global audience, he has discovered an extensive network of friends, admirers and collectors. For the past 19 years, his complex tangle of words, lyrics and other iconography, their meaning known mainly to him, have beckoned viewers, eyes squinted, to come closer and closer to his canvases.

Since he launched his career as a studio artist, Yanke says he has reconciled himself to the idea of achievement—he is, in fact, finally, a full-time, working artist. He concedes that he still finds it vaguely surreal to imagine that he has attained a modicum of artistic and financial success.

However, he does confide that he never takes anything for granted and is quick to remind himself that he’s just doing what he loves, each and every day—an immeasurable privilege often denied to many.

To collect the art of Tim Yanke, contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or sales@parkwestgallery.com.