Defining Cubism: Art’s Ability to Shatter and Build Again

“Nature morte au Crane” (c. 1960), Pablo Picasso

One of the reasons LEGOs are still popular today is their versatility. Those ubiquitous blocks can create anything: a race car, a vase, even the Eiffel Tower. But did you ever wonder where this idea of rendering life with blocks came from? Some might say LEGOs—and almost every modern art, literary, and musical movement—wouldn’t exist without Cubism.

What is Cubism, anyway? When we look at the world, we see complex shapes and curves, blending together to form three-dimensional objects. For example, in a computer, it takes equations upon equations to render the exact curves of a flower petal and just as much effort to realistically paint a petal on a canvas.

Instead of realism, Cubism takes real life, deconstructs it, and interprets it from infinite angles through geometry and abstraction.

“Harp Strings” (2006), Anatole Krasnyansky

The pioneering Cubists—Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque—saw the centuries of realist paintings as inadequate in depicting the three-dimensional world. In real life, everything moves and changes depending on the angle you view it. Cubism attempts to bring the 3D onto a 2D canvas, portraying motion, complexity, and the temporal experience without leaving the page.

After Cubism, the world of art and culture was never the same. Without Cubism, movements like Surrealism, Futurism, Dadaism, Constructivism, and modern art itself wouldn’t look the same. The writings of James Joyce and Gertrude Stein, which reorder language to find new meaning, relied heavily on Cubism’s influence. Igor Stravinsky, one of the most prominent 20th-century composers, cites Cubism as the inspiration for some of his most well-known compositions.

But how was Cubism created? And how did it become one of the most influential modern art movements to date?

The Birth of Cubism

At the dawn of the 20th century, the art world was still reeling from the groundbreaking work of Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and the Post-Impressionists. The middle ground between Renaissance-era realism and abstract art, Van Gogh and Cézanne used thick paint strokes and abstraction to depict realist forms.

“Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair” (c. 1877), Paul Cézanne

The way Cézanne specifically portrayed light made his shading look like blocks of color instead of smooth realism. Braque and Picasso, both living in Paris at the time, saw the early origins of Cubism in Cézanne’s work and began questioning how to push Post-Impressionism even further.

Many art historians credit Picasso’s 1907 work “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” as being the beginning of the Cubist movement. Painted in nine months after hundreds of sketches, “Les Demoiselles” depicts a brothel and five women with exaggerated, blockish features, emphasizing the women’s mask-like appearance and showing its subjects from multiple angles.

“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907), Pablo Picasso

Like most European art, Picasso’s inspiration was derived from non-Western sources and, as such, was treated as a new movement. “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was heavily inspired by African art, which Picasso encountered during a visit to the ethnographic museum in the Palais du Trocadéro months earlier. Although he denied the influence for a long time, in an interview with French writer Andre Malraux, Picasso eventually said “I understood why I was a painter” after that visit.

“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” was viewed as a rebuttal to Henri Matisse, the founder of Fauvism and a rival of Picasso’s. After “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Braque was astounded by the potential Cubism had to revolutionize the art world.

“Houses at l’Estaque” (1908), Georges Braque

In 1908, Braque submitted seven Cubist paintings to Paris’ Salon d’Automne. Five were rejected, so he removed them all from consideration. Matisse, who was on the jury, was quoted as criticizing the submissions as “entirely constructed of little cubes.” When his works were displayed at Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s gallery, art critic Louis Vauxcelles said “M. Braque scorns form and reduces everything–sites, figures and houses–to geometric schemas and cubes.”

These early reviews helped give Cubism its name.

Building Cubism Brick by Brick: The Founders

But Picasso and Braque didn’t just change the future of modern art with Cubism. They also refused to let their movement’s initial form restrict their future innovations. Picasso’s development as an artist actively created new waves of Cubism.

“The Harlequin” (1917), Pablo Picasso

After “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Picasso’s style was heavily rooted in Analytic Cubism, or the breaking down of the natural form into a new, geometric reality. In works like “Woman with a Mandolin,” the representation is still evident, but the abstraction brings out new discoveries in form.

On this phase of Cubism, Picasso said, “The viewer sees a painting in parts; one fragment at a time: for example, the head, but not the body, if it is a portrait; or eyes, but not the nose or the mouth. Consequently, everything is always right.”

“Nature Morte aux Poires et au Pichet” (1960), Pablo Picasso

After 1912, Braque played a large role in developing Synthetic Cubism—also known at Crystal Cubism—with Picasso and other artists of the era who were increasingly embracing the Cubist movement. These works take Analytic Cubism and splinter their real-world subjects into explosive-like compositions. The physical form is largely obscured, flattening the Cubist deconstruction of form into tighter compositions.

“Giroflee Bleue” (1963), Georges Braque

In this period, Braque brought the art of papier collé–“pasted paper”–and collage to the table, blending paint with other two-dimensional art forms. After serving in the French Army in World War I, Braque’s compositions became much freer, but his Cubist style continued to play in the freedom. Throughout his career, Braque brought Cubism to the worlds of lithograph, sculpture, illustration, jewelry, and decorative art, cementing his role in the history of modern art.

But Will It Blend?: Cubist Artists Who Defied Being Boxed In

The beauty of Cubism, and largely the reason for its lasting legacy, is its ability to work its way into other painting styles. A Surrealist artist, who attempts to unlock the subconscious through painting, could choose to render their dreamscapes through the geometric form, for example. The possibilities are endless.

Many artists learned from Picasso and Braque’s groundwork and created their own unique interpretations of what Cubism could accomplish.

One of those artists was Marc Chagall. Born in Vitebsk, Russia to a family of Hassidic Jews, Chagall mixed motifs of folklore and mysticism with the Cubist distorting of the human form. His work stands firm as a stellar example of what can happen when individuality meets pure talent. Against his parents’ wishes, Chagall studied art in St. Petersburg and eventually moved to Paris in 1910, where he was first exposed to the growing Cubist movement.

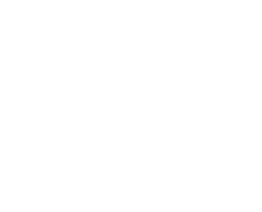

“Le Cercle Rouge” (1966, m.440), Marc Chagall

Chagall’s Cubism-inspired works from this era focus heavily on the raw emotion of love, a recurring theme for the rest of his career. “In our life there is a single color, as on an artist’s palette, which provides the meaning of life and art. It is the color of love,” Chagall said. “Only love interests me and I am only in contact with things that revolve around love.”

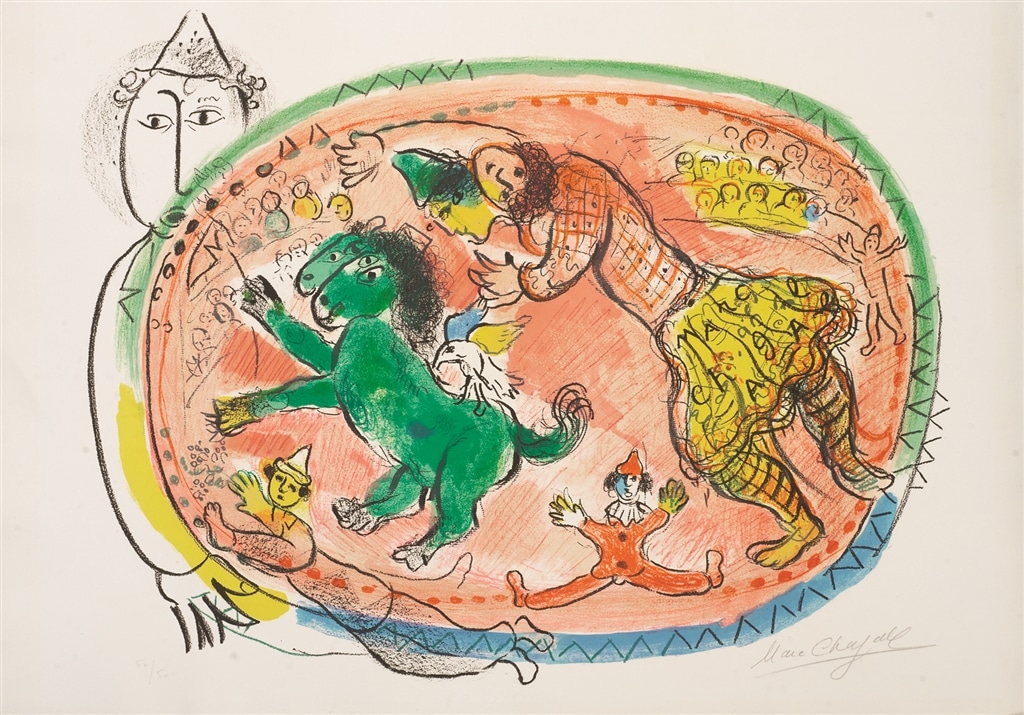

“Springtime on the Meadow” (1961), Marc Chagall

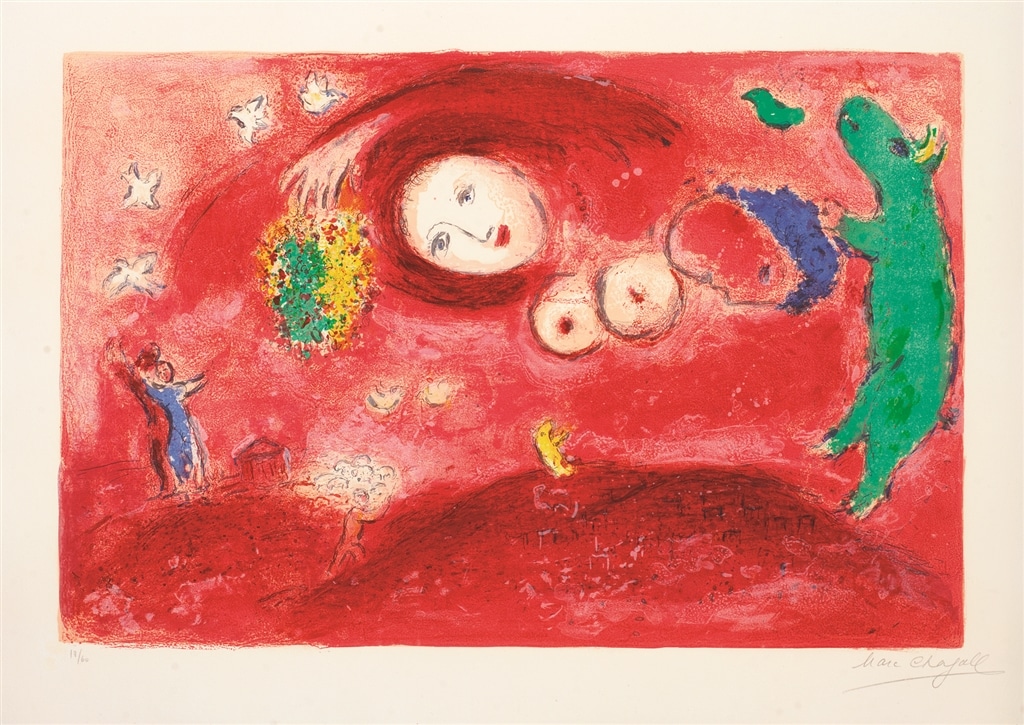

Victor Vasarely and his world-famous “Op Art” blended Cubism with Abstract Art to evoke complex emotions without words or even discernable images. Dabbling in the world of Post-Cubism early in his career, Vasarely conveys intense movement and hectic energy across his canvases. He also uses geometry to project order and logic to his audience amidst his Cubist forms.

Vasarely was consistently a fan of collaboration across disciplines and the pushing of boundaries, which makes perfect sense given his interest in Post-Cubism. He argued art must never stay stagnant, just as Picasso and Braque argued against the Renaissance-style realism of pre-20th-century art.

“Vega-Cor” (1990), Victor Vasarely

Vasarely said, “all architects, painters, sculptors must learn to work together. It is not a matter of negating the masterpieces of the past but we have to admit that human aspirations have changed. We must transform our ancient way of thinking and conceiving art … Art must be generous.”

Carrying the Torch: Cubism Today

Much like Levi’s jeans and Converse high-tops, Cubism never goes out of style. Today, many artists stand as shining examples of how Cubism lives and breathes in the 21st century.

Romero Britto, for example, grew up in Brazil painting on whatever he could find—newspaper, scraps of cardboard, anything. When he travelled to Europe to study art, Britto saw Picasso’s work for the first time and was profoundly inspired. Both artists took the familiar and turned it on its head, creating a wholly original art form beyond its years.

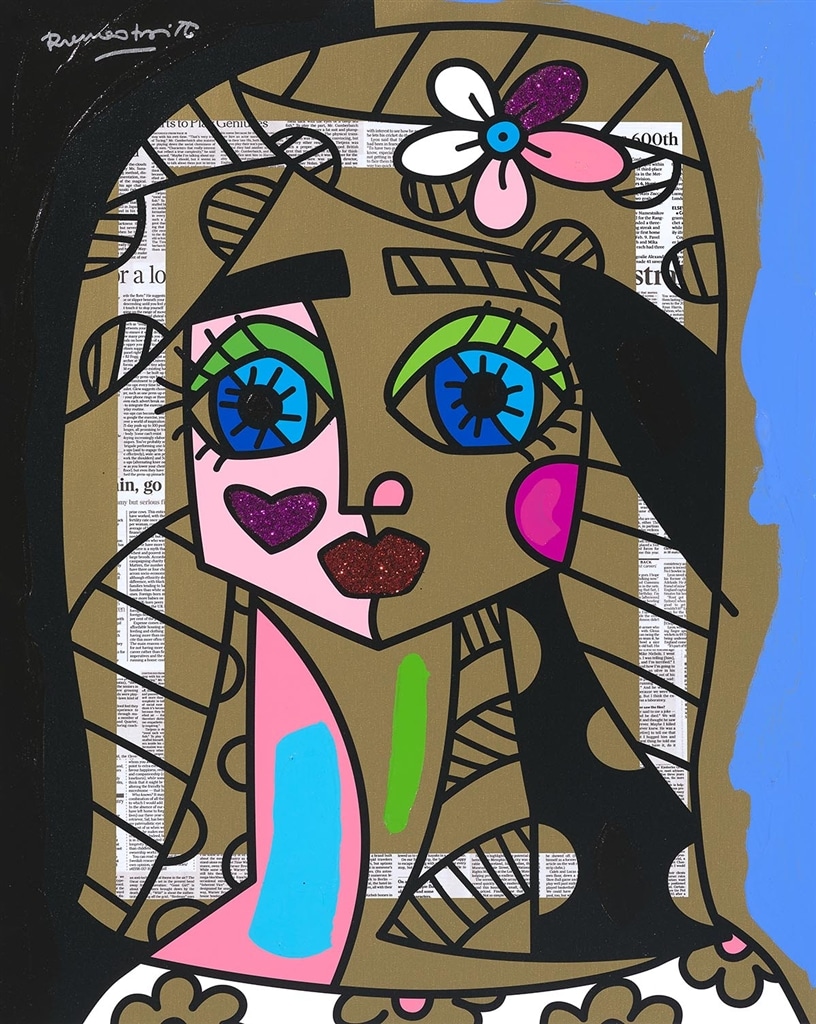

“Blue Couple” (2016), Romero Britto

In his painting “Blue Couple,” Britto uses Picasso’s two-faced human distortion technique and elements of Pop Art to create a cartoonish sense of love and belonging. By utilizing Cubist theory, the viewer can interpret the lovebirds from multiple angles, seeing how their faces, arms, and torsos interlock and fit together like puzzle pieces.

“I hope when people see my art they have a big smile on their face and a huge one in their heart,” Britto says.

“Venus XXIV” (2018), Romero Britto

Anatole Krasnyansky brings Cubism to the worlds of watercolor and printmaking using texture to remind audiences of the beauty in the world’s traditions and cultures.

Krasnyansky’s work emphasizes the dualities of time, reality, texture, and color. His Cubist figures are often set in front of realist backdrops, emphasizing the relationship between the old and new worlds. Similar to Britto’s Cubist style of painting figures with multiple faces, Krasnyansky does this to make a statement about how humans adapt depending on the social situation.

“Dancer” (2006), Anatole Krasnyansky

“We all have many faces,” Krasnyansky says. “It depends where we are and who we are with, but in each case, we adapt, putting on a mask. That is why, in my paintings, my figures have a multiplicity of faces.”

Another artist who benefited from an early exposure to Cubism is Peter Nixon. Though classically trained as an artist, Nixon realized early in his career that his work was lacking movement and energy. To combat this, he began auditing dance classes, studying the figures and forms of the dancers.

The challenge of capturing the fleeting gestures of dancers as they moved about instilled in his work a sense of dynamism and a multiplicity of viewpoints, akin to the concepts of Cubism.

“Dance Troupe II” (2006), Peter Nixon

“Figure studies can look as stiff as statues so I needed the suggestion of human beings in motion and a vibrancy to bring the pictures to life,” Nixon said. “This, coupled with my interest in Cubism, enabled me to formulate an approach to movement in my work that became what I call my ‘sketch style.'”

“This energy translated itself into themes about human beings at the peak of accomplishment; so the pictures became about enthusiasm, joy, love, music and dancing–fleeting states of mind that produce a feeling of being most vividly alive.”

Art is all about seeing. Whether you’re looking at a vista, a global issue, or an expression of self-identity, art pushes the audience to consider a subject from a variety of angles. Through Cubism, modern art reached a new peak in innovation and three-dimensional representation.

Instead of looking at a flat image, Cubism allows viewers to dive into a painting, walk around, and see what they find. The beauty of it all is that no two people will ever discover the exact same thing.

If you’re interested in collecting Cubist art or want to know more about artists who specialize in Cubism, register for our exciting online auctions or contact our gallery team at 1-800-521-9654, ext. 4 or at sa***@*************ry.com.

LEARN MORE ABOUT ART AND ART MOVEMENTS:

- What Is Surrealism? How Art Illustrates the Unconscious

- What Is Abstract Art? How Artists Make Something Out of Nothing

- Chris DeRubeis Talks Abstract Sensualism® and Style

- Discerning Eyes, Abstract Musings: Artist Tim Yanke Comes of Age

- Lebo Breaks Down His Postmodern Cartoon Expressionism

- How Artist Slava Ilyayev Brings Modern-Day Impressionism to Life