Why Animation Art is One of the Most Important Art Forms of the 20th Century

“Warner Brothers Gang” (2015). Seriolithograph in color on paper.

Animation art is beloved around the world, but, if we’re being honest, it’s also underappreciated.

How is that possible? How can it be adored and taken for granted at the same time?

It’s easy to see how much people love animation. Animated films are hugely popular worldwide. They’re often the first movies we fall in love with as children, introducing us to iconic characters like Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, and so many more.

However, even though those movies and cartoons hold a special place in our hearts, we often overlook the sheer artistry and technical skill that goes into creating animation. Those animated classics aren’t just artistic masterpieces when they’re viewed as a whole. Each animated film is made up of thousands of individual masterpieces, flicking by at 24 frames a second.

“Dink, the Little Dinosaur: Together” (1989). Hand painted production cel with color background.

It’s for those reasons—and many others—why Park West Gallery is proud to offer an impressive collection of animation art.

Initially, Park West offered unique production cels from Warner Brothers, Disney, Hanna-Barbera, and other studios. We later eventually expanded our offerings to include art from most major animation studios and works by renowned animation artists. These works can take a variety of forms, including production cels, sericels, and hand-painted limited edition cels, among others.

“Snow White & Doc” (1990). Sericel.

But, even though everyone loves animation, Park West wants to make sure our collectors recognize the importance of animation art too.

Along with jazz and the Broadway musical, animation is one of the few uniquely American art forms. Animation, as we know it today, was largely created in those early studios in Hollywood, and it has since become a critical component of art, entertainment, culture, and business. There is nothing else like it on Earth.

Animation also exists as a truly artist-driven medium. Some of the greatest artists of the past hundred years have either worked in animation or have been inspired by animation art.

Still don’t believe us? Here are two examples that will give you an idea of just how influential animation has been in the world of contemporary art:

WHEN SALVADOR DALI MET WALT DISNEY

Legendary Spanish artist Salvador Dalí is remembered as one of the innovators of Surrealism, but, when he first came to the United States, he found a kindred spirit in one of the founding fathers of animation.

In 1937, in a letter to André Breton, author of the Surrealist manifesto, Dalí wrote, “I have come to Hollywood and am in contact with three great American Surrealists—the Marx Brothers, Cecil B. DeMille, and Walt Disney.”

If anyone doubts the validity of animation as an art form, keep in mind that Dalí—one of the most famous fine artists of the 20th century—considered Disney’s animation to be on par with his own artistic endeavors.

Disney admired Dalí’s work too and, after meeting at a Hollywood party in 1944, they decided to collaborate on a project.

The partnership between Dalí and Disney resulted in the short animated film “Destino.” Dalí, along with famous animator John Hench, created 22 paintings and over 135 storyboards, drawings, and sketches for the project, calling it “a magical exposition on the problem of life in the labyrinth of time.”

The project was unfortunately halted before production was finished and languished in the Disney vaults for years until Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew, finally resumed production in 1999. “Destino” was released in 2003, garnering numerous awards and an Academy Award nomination.

The art Dalí created for “Destino” is breathtaking. Park West is now offering etchings, lithographs, and serigraphs from Dalí’s original art for “Destino”—both his pre-production art and art capturing quintessential moments from the film.

Dalí’s paintings and sketches from “Destino” have toured museums and galleries all around the world, and they continue to tour to this day.

They have been featured in the exhibitions “Dalí: Painting and Film” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and “Disney and Dalí: Architects of the Animation” at the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

When Dali’s original “Destino” art is not on display, it is returned to Walt Disney Studio’s Animation Research Library (ARL). The ARL is the largest repository of artwork currently in existence, comprised of over 65 million original works.

PATRICK GUYTON: AN EDUCATION IN ANIMATION

Patrick Guyton is one of the most exciting young artists working today. His work weaves together a host of influences—Japanese gold-leafing, classic Flemish glazing techniques—but one of the biggest influences on his artistic style is his background in animation.

He started as a commercial artist, but, in 1997, Guyton jumped at the opportunity to work as a background painter for animation legend Chuck Jones.

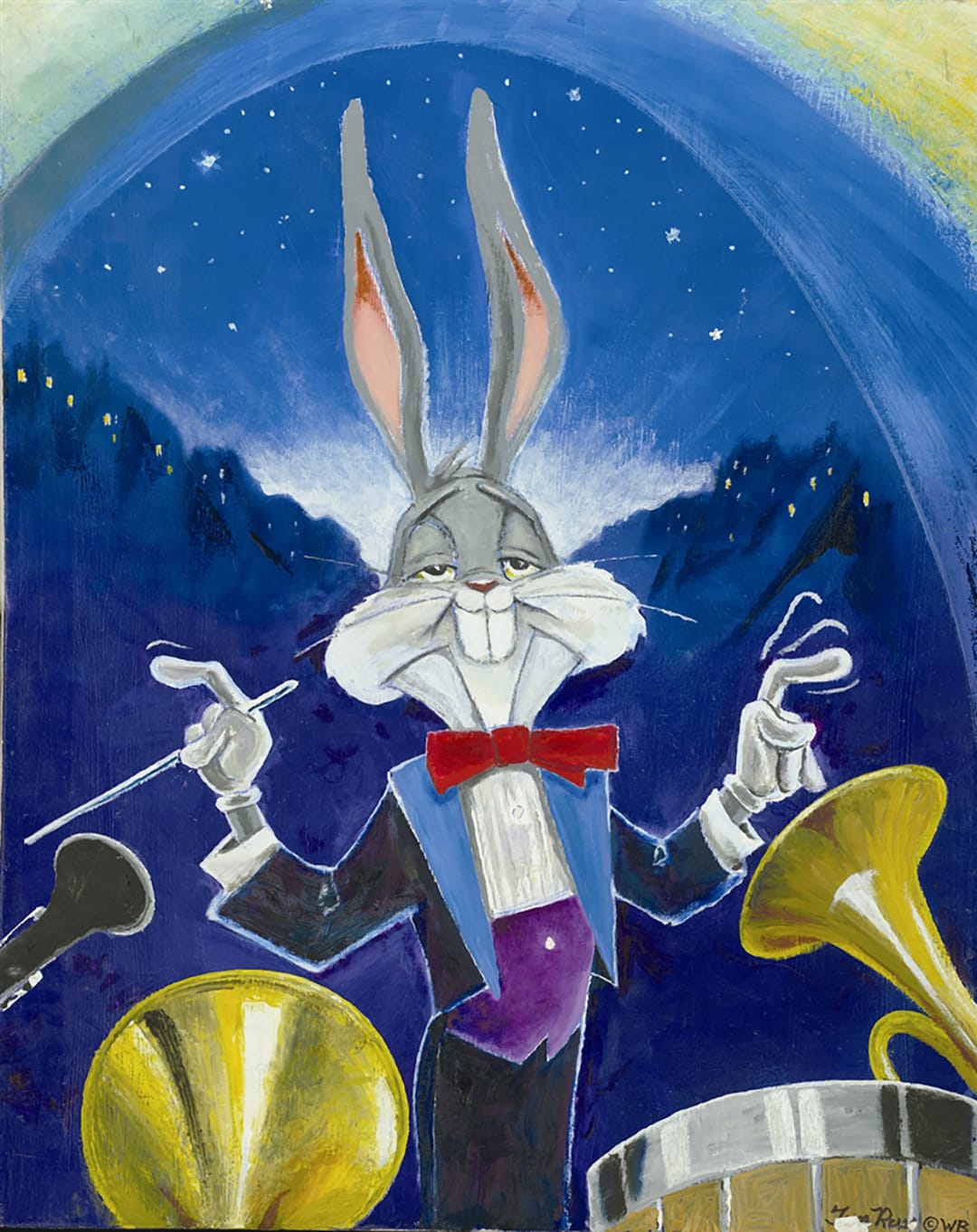

Even if you’re not familiar with his name, chances are, you’re familiar with Jones’ work. He’s responsible for some of the most famous Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck cartoons of all time. He’s a giant, both in animation and in modern popular culture. Hollywood icons like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg frequently cite Jones as an inspiration.

But Chuck Jones might be most famous for creating scores of unforgettable animated characters, such as the Road Runner, Wile E. Coyote, Elmer Fudd, Pepé Le Pew, Marvin the Martian, Michigan J. Frog, and so many more.

“Duck Dodgers” (2016). Sericel with color background.

Throughout his career, Jones received eight Oscar nominations, won three Oscars, and was presented an honorary Academy Award in 1996 for his distinguished career.

It’s easy to see how working with Jones would be a dream come true for a young artist like Guyton.

Guyton later went on to work with other animation legends, including Robert McKimson Jr.—son of acclaimed animator Robert “Bob” McKimson—and Maurice Noble, the celebrated animation background artist who worked on Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” “Bambi,” “Dumbo,” and “Pinocchio.”

This experience working in animation helped shape Guyton’s personal artistic style. By painting animation celluloids, Guyton gained invaluable first-hand knowledge of how to effectively use negative space, layering, and minimalism.

“Bugs Bunny,” Tom Ray. Acrylic painting on canvas.

Guyton eventually left the animation industry to begin his career as a fine artist, but he will never forget the lessons he learned from some of animation’s greatest Golden Age geniuses.

“They are underappreciated, probably because they did cartoons, but they’re legends nonetheless, and I believe in those years I learned more than what art school could’ve ever shown me,” Guyton says.

As we mentioned, those are just two of many examples of animation’s influence on contemporary art—this doesn’t even get into animation’s impact as its own unique art form.

The background art, design artwork, hand-painted production cels, not to mention the final animation—every aspect of the production of an animated film is a work of art, in and of itself.

“Charlie and Snoopy’s Ride” (2006), Etching in color on wove paper.

It’s also important to note that the world of animation is changing. Virtually every major animated film today is created via a computer, so that iconic background and cel art simply doesn’t exist anymore.

The next time you’re viewing a classic Disney movie or revisiting a favorite cartoon from your childhood—marveling at the perfect timing of a Chuck Jones gag or a brilliant background by James Coleman—take a moment to appreciate the artistry behind what you’re watching. You might not be able to see the technical virtuosity in each and every frame, but you can definitely tell that it was created by artists who love what they do.

If you’re interested in collecting animation art, register for our weekly live online auction or contact our Gallery Sales team directly at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or sales@parkwestgallery.com.