A Brief History of Landscape Painting: Michael Milkin and Igor Medvedev

While modern fine art collectors are seemingly drawn to the beautiful French countryside works of Monet, Pissarro, and Cezanne, this wasn’t always the case. The tradition of landscape painting, in any form, was born from centuries of evolved painting styles, beginning with the tinted walls of the ancient Greeks. Adorning their walls with beautiful gardens and rolling hills was initially common but eventually these scenes became the backdrop for religious stories. Not until the Italian Renaissance in the sixteenth century was this technique revived, brought to height by Leonardo da Vinci’s portraits.

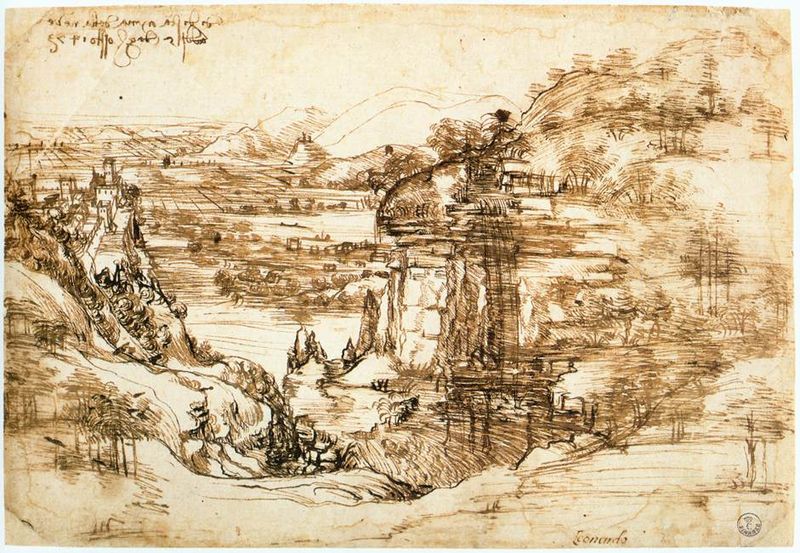

“Arno Valley Landscape” (1473), Leonardo Da Vinci (Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

Leonardo was notorious for incorporating landscapes behind his subjects in the foreground, utilizing dramatic chiaroscuro and rugged terrain, possibly as psychological cues. As the Renaissance revived the classical ideals, naturalistic elements like scenery and landscape sparked a new interest in studying nature and its importance.

Derivative of the Dutch word, landschap¹, idealized landscapes truly began in the Netherlands, the location of a steadily growing population of Protestants that wanted a secular option to the contemporary religious subject-matter. Aelbert Cuyp was one of the most poetic Dutch landscape artists, drawing from his surroundings to paint bright and imaginative scenes. By the seventeenth century, the landscape was perfected, displaying an idealized, classical harmony where Nature was balanced and serene, evoking a classical simplicity. Landscapes were still not the highest form of painting recognized by the royal academies, but they remained popular, steadily growing in importance. Finally, late in the eighteenth century, the Academy recognized landscapes as historic and important, documenting nature as an educational study. This led the way for one of the first genres of American art, using the landscape as a form of American history.

“Italian Landscape” (2010), Igor Medvedev

When the Hudson River School began painting in the middle of the nineteenth century, they believed that by painting American landscapes in epic proportions (canvases the size of large walls) it could instill a sense of the Sublime. The dramatic vistas and beautiful scenes did two things. Since history painting had been at the top of the artistic hierarchy until that time, yet America as a (European) civilization was just beginning, artists used depictions of the land as its own form of history painting. By doing so, these impressive paintings became their own kind of secular faith, glorifying a fledgling country with the beauty of its lands. Painters like Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church used the vast and open expanse of land to convey emotional and romantic notions of the new frontier.

“Tuscany” (2010), Igor Medvedev

By the late nineteenth century, some of the world’s most beloved landscapes were being painted by artists like Van Gogh and Monet, practicing the technique of en plein air, or painting outdoors. Now that pre-mixed boxed paints were readily available, the artists could travel outdoors to paint amidst a more natural setting, further developing the quickly changing social customs and the idea of the weekend. The bourgeoisie could take the train to the countryside on the weekends, escaping the drab of the city. Moments like these were captured by the Impressionists and their contemporaries, documenting this new lifestyle in paintings of landscapes and social scenes. Their modern masterpieces broke ground for today’s contemporary landscape artists like Michael Milkin and Igor Medvedev.

“Tranquil Sailing” (2017), Michael Milkin

Ukrainian artist Michael Milkin interprets nature through his unique depictions of birch trees and flowers throughout the seasons, capturing the majesty and freedom of an autumn evening, a hot summer afternoon, or a snowy morning. He concentrates on still lifes and landscapes, painting with acrylics and oils with thick, dramatic brushwork and brilliant colors. Milkin has always found inspiration from the artwork of Impressionists such as Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Paul Cézanne. Milkin portrays the beauty of birch trees across various seasons and, like the Impressionists, places an emphasis on light. Russian landscape artist Fyodor Vasilyev has greatly influenced Milkin as well, specifically his compositions and color palette.

“The View Beyond the Birch Trees” (2017), Michael Milkin

The late Igor Medvedev used his landscapes to document the quickly changing topography of coastal villages. This California artist didn’t attempt to copy nature in his paintings or to describe in the manner of the photo-realists. Instead, he constructed painterly compositions that direct the eye, moved by their visual drama and hidden mysteries. He described these hidden instances as “moments of intimation” and aspires to reach “a kind of agreeable unease.” His scenes are landscapes in which he immerses himself – passing moments in Greece, Italy, Spain, Morocco, Turkey, and Africa. Timeless and alluring, these places are captured for his viewers – insight into a world they may never see first-hand – and soon, might be gone forever.

Inspired by the rapidly disappearing towns and villages of the Mediterranean and beyond, Medvedev urgently documented with a theme of ecological and cultural preservation, listening to the bulldozers as he painted. Within each piece lingers a sense of balance, wonder, and curiosity, holding the viewer captive as he slowly breathes in the serene colors and harmonies.

“Entranced” (2005), Igor Medvedev

¹ The J. Paul Getty Museum’s “Brief History of the Landscape Genre,” originally meaning “region, tract of land.”

To collect artwork from either Michael Milkin or Igor Medvedev, attend one of our exciting live online auctions or contact a gallery consultant at +1-248-354-2343 or at sales@parkwestgallery.com

Follow Park West Gallery on social media

Related Articles