In Memory of Charles Bragg (1931-2017)

By Morris Shapiro

Charles Bragg was one-in-a-million. I’ve never known anyone like him, nor is it likely that I ever will again.

He was an amalgam of many parts: a supremely gifted visual artist, a storyteller and a witty writer, a deeply educated classicist, a keen observer of human nature and a comic. All of these qualities came together in a man of uncommon warmth, uncompromising dedication to his craft and a determination to keep on moving and growing as an artist and a man. He worked every day — up to his very last.

Charles pushed away compliments and became uncomfortable when I spoke publicly about his importance as an artist of our time. But this remains true. His work resides within a long narrative tradition that begins with Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel, and extends through Francisco Goya, William Hogarth, Honoré Daumier, into Al Hirschfeld and Ralph Steadman. Each of these artists in his own way cast an eye on the society of their times — the institutions, the culture, the behaviors of the classes, religion, work, life, death, ambiguity and irony. In Charles’ work there was first a humorous delight as we got the “joke,” but then continued to the deeper message and a proffered mirror. Charles said of his work that its purpose was to “amuse and punish.”

The circumstances of his life formed the man and artist he was to become. His childhood travelling with his vaudevillian parents placed him backstage, looking out at the audience from behind the curtain and implanted a skewed perspective of the showbiz world. In lighter moments, he claimed his parents single-handedly killed Vaudeville.

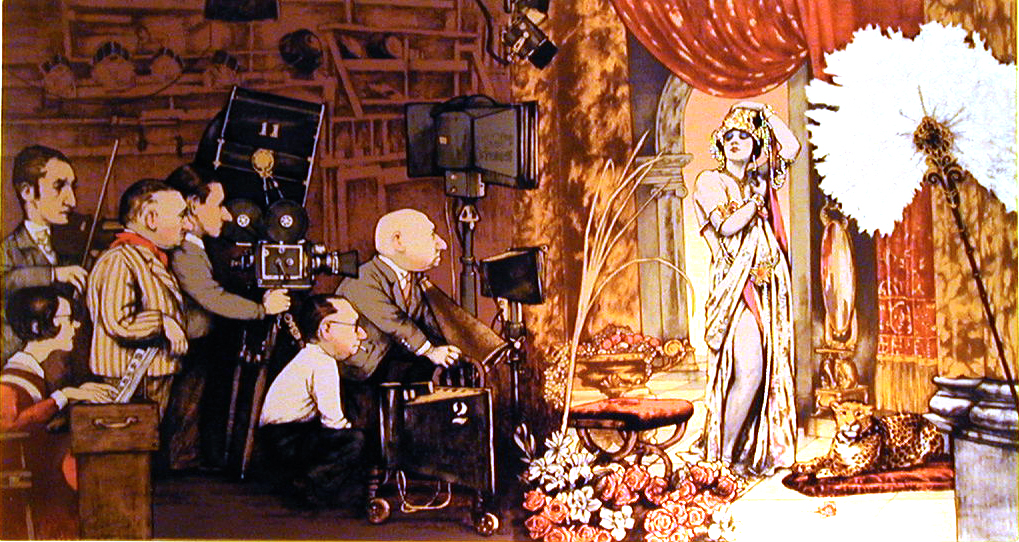

Charles formally studied art and the classics honing his technique as a draftsman, painter, printmaker and sculptor. He developed his technique to an astonishing degree with an “old masterly” quality in his paintings, often belied by the upstaging of his subjects and messages. I was always particularly taken with his graphite drawings. For me, these were the truest glimpses into an artist’s gifts. He preferred drawing on mylar, with its textureless surface where he could move from pin-point detail to soft atmospheric rubbings for shading and lighting nuances. In 2011, we sold his large, preparatory drawing for “Screen Goddess,” one of his most famous works. I couldn’t take my eyes off of this exquisite drawing when I first saw it. Apart from the subject of an early Hollywood movie set, I thought I was looking at a drawing that was at least 400 years old because it exploded with so much virtuosity.

“Screen Goddess” Charles Bragg (the completed painting).

He went on to try his hand at different career paths: truck driver, automobile dealer, stand-up comic, among others, but thankfully for us all, he returned to his love of art, and settled in California to build his body of work and reputation. Charles created wonderful ink-drawings for Playboy magazine that appeared in the margins of the articles. He referred to these tiny erotic musings as his, “Little Naughties.” As books and articles on his art were published and his PBS documentary aired, and the galleries all over the United States were showing his work, his reputation grew immensely. Charles’ body of etchings became wildly popular in the 1980s and ‘90s, in particular his commentaries on the legal and medical professions. There was a time I recall, when it was de rigueur for every attorney’s office to have a least one Bragg in the back where the clients couldn’t see it.

Around the turn of the century, Charles essentially dropped out of sight. Many believed he had passed, but in reality, he had found for himself the ultimate financial situation for an artist: an exclusive patron. This individual, who committed to buy every painting Charles created, allowed him to relax and relieved him of the financial burdens and distractions of sales efforts and the promotion necessary for an artist’s survival. Between his patron and his close friend — the comedian and actor, the late Jonathan Winters — all of Charles’ works were consumed. The body of paintings he created at this time is extraordinary. It ranges from the playful and even whimsical—a mouse wearing a tuxedo playing a concerto on a grand piano— to his biting satirical works on organized religion and government—all realized through his brilliant technique.

“Parade #1” (2011), Charles Bragg

In 2010, Park West President Marc Scaglione and myself hit on the idea of reaching out to Charles again (we had done business together in the 1980s and ‘90s). We contacted him to see if he’d be interested in appearing at some of our private events on cruise ships. Charles was interested, and Marc and I went to visit him and his wife Margaret at their apartment in Beverly Hills, California. It was a delight to enter into his home and his world. His studio occupied most of the living area and his stock room was adjacent. On the easel was an oil painting he was working on, called “Parade #1,” which was snapped up the first time we showed it. Next to his painting table was laid out a sculpture — a sort of colorless diorama — of his masterpiece concept “Asylum Earth,” comprised of dozens of tiny figures, which the viewer looked down upon, all engaging in riotous activities and crazy interactions with each other. Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights” through the lens of Charles Bragg, transported into the 21st century.

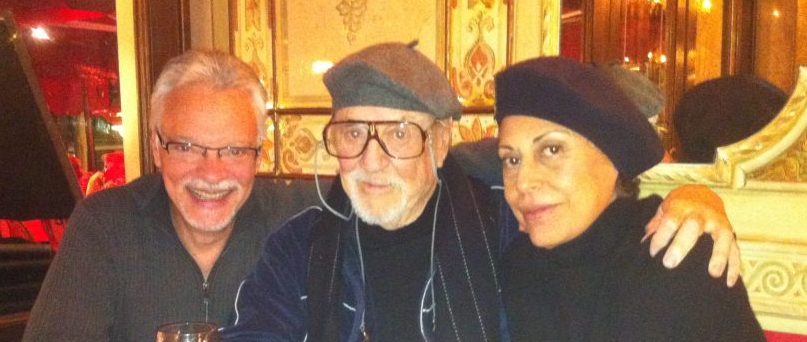

Morris Shapiro with Charles Bragg and Bragg’s wife, Margaret, in Venice.

Thus began our renewed relationship: Charles Bragg 2.0. For nearly six years we brought Charles and Margaret out to sea and land a few times each year, to meet our clients and create new fans and collectors for him. Charles worked hard in preparation for each of these appearances. Our typical collection consisted of approximately 20 oil paintings, many of which paid homage to his heroes: Pablo Picasso, Rembrandt van Rijn, Henri Matisse, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and his beloved Claude Monet. Also included were a series of highly detailed, mixed-media works on colored paper (in the last two years Charles was enamored with Asian subjects in this medium), along with at least a dozen drawings and his famous etchings. Charles’ art was not always easily accessible and certainly not decorative in any sense. It was to be contended with, and it challenged the viewer, no matter how humorous or innocuous at first glance. But the response from our guests was always positive. The truly astute collectors realized how rare and important and opportunity it was to meet him and see a world-class collection of his works. And they took advantage.

Our introductions of Charles were always the evening before his auction. We previewed a selection of paintings and talked about his extensive credentials, but the coup de gras was when he tottered up to his lectern (from a wheelchair in his last days) and delivered his monologue. This was the moment when everyone in the room realized the talent and greatness to which they were being treated. He usually spoke for about 30-40 minutes. In deadpan, self-deprecating prose, he covered such topics as his health (for a perspective on his prices, he told everyone his age, and joked that his blood-pressure was “through the roof,” and that he was wearing a diaper!); some musings on the great philosophers’ quotes, with his own spin, of course; stories about his days as a young artist in Paris, paying for his restaurant meal with a drawing on the tablecloth and then being charged for defacing restaurant property; and a visit to the Louvre, where he put up one of his own paintings on the wall with two-sided tape and instantly doubled the Louvre’s collection of American art (“Whistler’s Mother” is the only American painting in the collection); and finally his great story about “Art Heaven.”

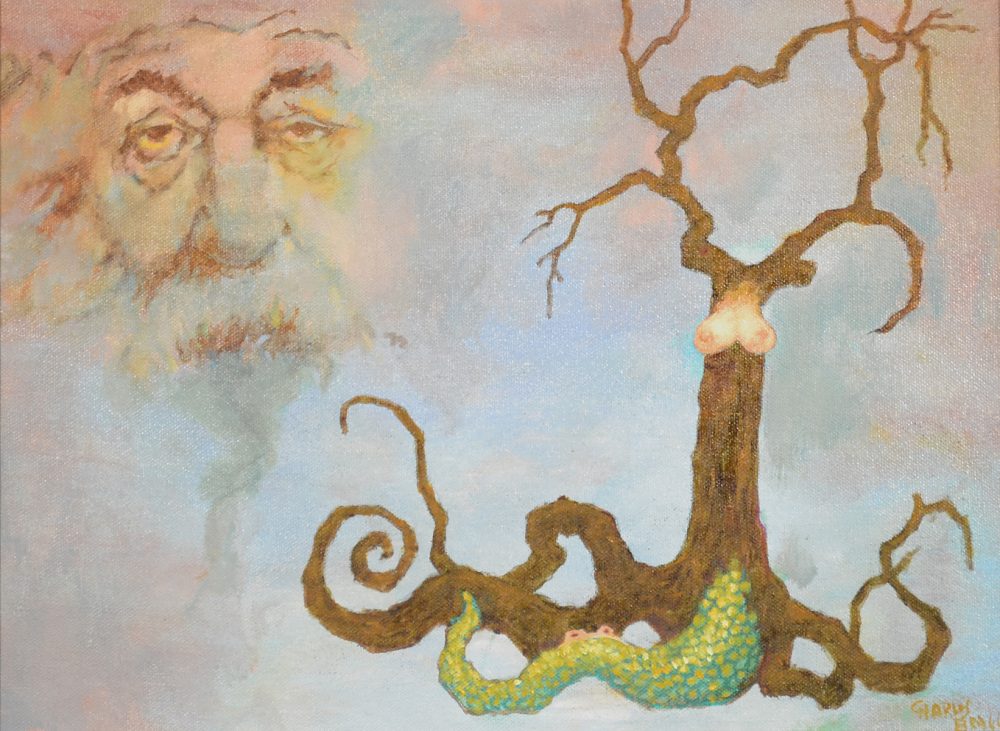

“In the Beginning There Were Mistakes” (2011), Charles Bragg

The story, which appears complete in the brilliant and hysterically funny collection of his writings, “Asylum Earth,” recalls a dream in which after he dies Charles hopes to be admitted to Art Heaven. He walks through the corridors and peeks into the shared studios of the masters and must ultimately present his portfolio to a group of them, including Goya and Rembrandt. While looking at one of his paintings, Rembrandt asks, “What were you thinking about when you made this?” to which Charles replies, “I was poor and probably thinking about my car payment.” Rembrandt quietly contemplates the work and says, “Yes, I can see the desperation in the brushstrokes…” Finally, the group discovers a painting that interests them all. It depicts God as the wizened, bearded visage of the ages. He holds a tree with two large breasts protruding from the trunk and with a long serpent-like tail. The group inquires about it. He replies that when God made the world Charles suspected there were certain creations that might not have gone as planned. Thus, he titled the painting, “In the Beginning there were Mistakes.” The group chuckles all around and decides Heaven needs a little levity. They decide to let Charles in, at which point he awakens from his dream.

The obvious poignancy of the story has been resonating all over these last few days among those who knew him and were treated to this tale at one of his appearances. Many have reached out to me with words of comfort, as they knew how much I adored the man and affirmed that “Art Heaven” is where Charles is painting today.

Over these last five years, I savored every moment that I was with him and Margaret, as I knew this day was not far off. With Charles, I laughed longer and harder than with anyone I ever knew. Everyone around him did too. We had many wonderful adventures together: dinners from Venice to San Juan; discussions on art, life and ideas, always brimming with ideas. He was usually drinking his beloved gin martinis, which when placed in his hands, he would announce to all, before the first sip, “See ya later!”

Charles Bragg and Morris Shapiro. “With Charles, I laughed longer and harder than with anyone I ever knew.”

I always described Charles as an “American National Treasure,” which I believe became truer with each passing year. And now, like so many great ones before him, he belongs to the ages. I know he’s painting alongside his heroes now, occupying one of those studios in “Art Heaven,” and I know he’ll be one of the committee passing judgments on the next generation of applicants. I’m sure he’ll be lenient though. He was such a sweet soul.

Rest in Peace, Charles Bragg.