The Rise and Reign of Modern Art

In the last 150 years alone, the art world has taken a series of tenacious twists and turns. What was once defined by ornate encasements, master apprenticeships and royal commissions transformed into an unwavering suspicion that art, perhaps, could be worth more than what meets the eye. Today, art can lend significance by simply provoking a thought. It can even be an everyday object.

So when did art take its first turn?

1839 set an artistic precedent for the ages. Though likely considered to be just another invention at the time, the introduction of commercial photography forged the pace of the modern era, where art history embarked on a clever and irreversible course.

With photography, history was no longer bound to a likeness in paint. The camera could do a better job capturing the people and places of the moment, and it could do it faster. As the camera quickly became the world’s most compelling and precise documentarian – what was to become of the art world?

Art, no longer servant to the grandiose aristocracy of visual culture was transformed, instead, into a philosophical relic. Art could be brutal, opinionated, political, honest, and lucid. It could be anything for that matter. But it didn’t have to be wholly representational.

Thus began the rebirth of art in the modern era.

Though the “What is Art?” debate persists among scholars, theoreticians and curators, alongside those humble holiday discussions between aunts and uncles, there are some unwavering tenets when it comes to understanding and appreciating modern art.

Below is a brief historiography of three artistic concepts that altered the world’s visual landscape in the modern era: color, dimension and media.

Color:

For centuries, color merely acted as an aid to the artist’s intent: Baroque portraits of royal families were inlaid with slivers of gold and shaded with jeweled hues to symbolize their eternal authority, a pop of rose on a portrait would give the illusion of good health, or the absence of color would anticipate a more formidable fate in the Romantic era.

Color, too, was re-interpreted in the modern era.

In the late 19th century, French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists began to employ a more liberal study of color onto their canvases. Speckled skies of blue and lavender were contemplated less deliberately, offering an emotional lightness to art history’s canon.

The Fauvists of the early 20th century to the Minimalists of the 1960s took a different approach to color altogether, one where color no longer assisted the composition, but acted as a powerful subject matter in itself. In a Minimalistic composition, the relationship between two colors became a dynamic dance and method of storytelling.

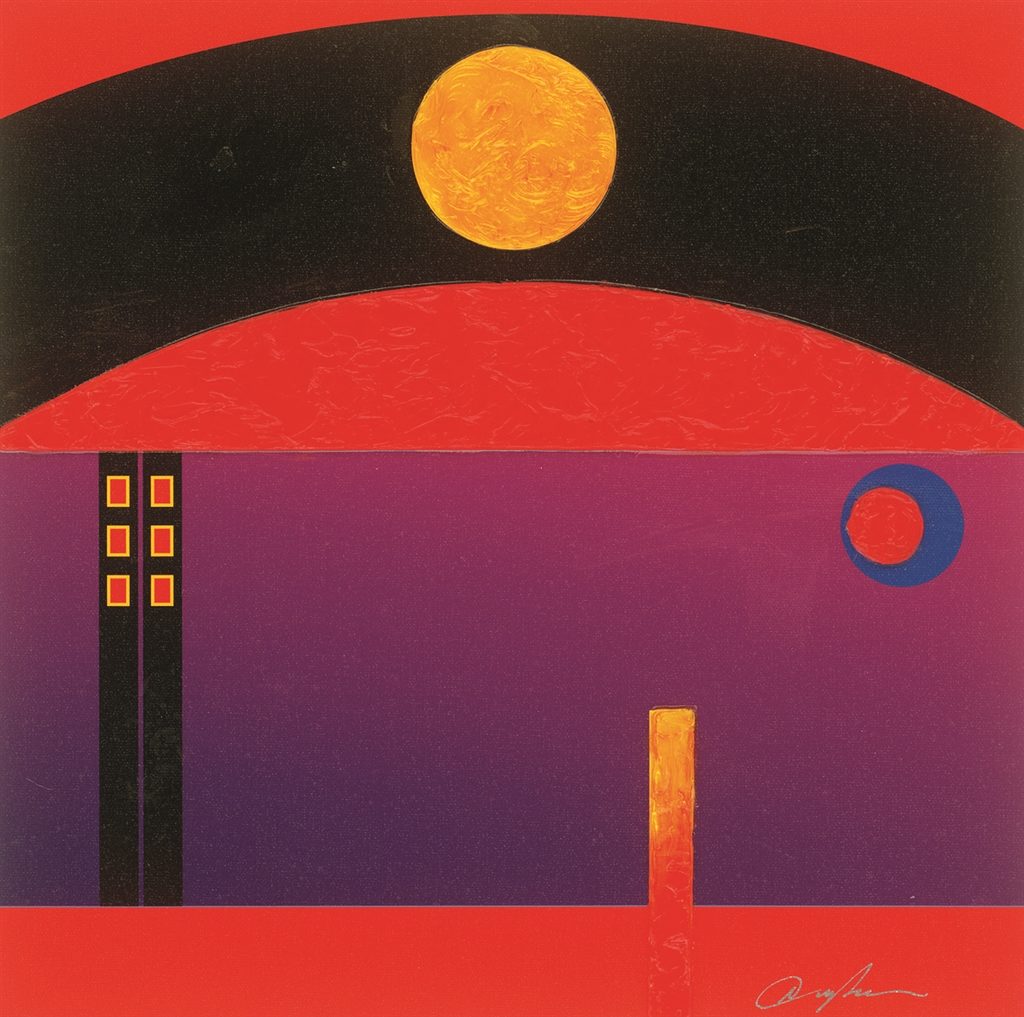

“American Icon – City Lights” (2006), Dominic Pangborn

Take the artwork of Detroit-based artist Dominic Pangborn, who translates the energy of a bustling city into a series of colored shapes and planes. He employs color not just to highlight the composition, but makes it the protagonist of the composition, rendering a most complex city into its fundamental parts.

Dimension:

Artists quite literally shattered the notion of dimension during the turn of the 20th century. The Renaissance initially offered essential innovations toward perspective, allowing artists to convey depth and dimension with unprecedented realism for the first time. In the early 20th century, however, artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque ushered in Cubism, an art movement that redefined dimension as jarringly hyper-real

Cubism gave artists the ability to depict subjects in every dimension finitely possible. No longer bound by one dimension, artists ferociously deconstructed the angles, lines and shapes that order our lives, lifting them from their neat upbringing and casting them into a fractured prism.

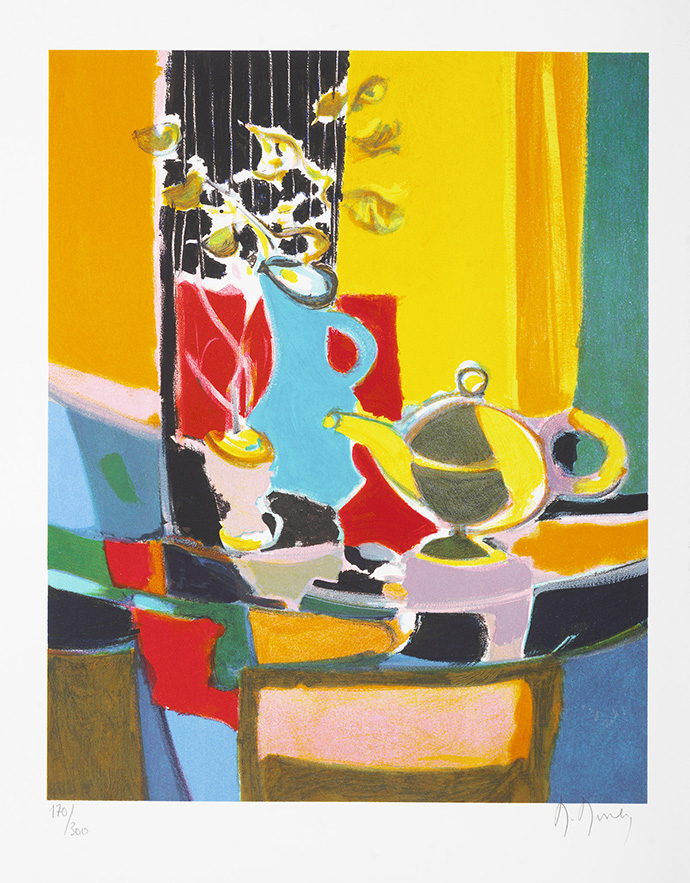

“Le Pichet Chinois” (2004), Marcel Mouly

Marcel Mouly, renowned French lithographer and one of the last artists to exhibit alongside Picasso, developed a reputation as one of the most important modern Cubists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Mouly’s compositions melodically re-interpret space and color into playful combinations.

Media:

A conversation on the fundamental direction of art would be nothing without considering the materials, or media, used. Whether contemplating ancient cave drawings, Roman sculptures, or Venetian frescoes, centuries of art history reinforced the notion that art could only be materialized through a limited list of supplies: paint, pigment, marble and bronze. Only did the rise of photography privilege the novelty of new materials.

Modern art, thus, became defined by an unmediated freedom of expression, not only in subject matter but material.

Some artists in the beginning of the 20th century relished the shock-value of the Ready-Made, exhibiting urinals, shovels and bicycle seats as a symbol of artistic rebellion. Later, Pop-icons like Andy Warhol fetishized celebrities and grocery store items like Brillo pads and Campbell’s soup cans, offering a statement on the fickleness of consumer culture.

“Bubbles” (2010), Yaacov Agam

Another renowned artist, Yaacov Agam, widely regarded as one of the fathers of the Kinetic Art movement in the mid 20th century, used innovations in media to encourage viewer participation and contemplate the dimension of time. Agam’s creation of the Agamograph – a multiple series of images viewed through a lenticular lens – exemplifies how technology offered a means to expand the depth of the canvas.

To learn more about Park West Gallery’s mission and talented family of artists, join the Park West community by contacting a gallery consultant, visiting one of our 100 onboard galleries or our flagship gallery in Southfield, Michigan.