7 Creepy Works from Francisco Goya’s ‘Los Caprichos’ Series

Detail from “Se Repulen” (They Spruce Themselves Up, c. 1799). Etching from Francisco Goya’s “Los Caprichos” series.

Francisco Goya is one of the most important Spanish artists of the 18th and 19th centuries. He was a satirist, he was a genius, and he also had a definite taste for the macabre. When art lovers describe Goya’s later works, in particular, you’ll frequently hear the words “unsettling” or “creepy.”

Goya wasn’t afraid to be creepy, especially in his famous “Los Caprichos” series, which he began sketching shortly after becoming ill in 1792. That illness sparked a wave of creativity that led to the decidedly darker style the artist would display in “Caprichos.”

His “Los Caprichos” etchings are made up of 80 plates completed between 1797 and 1799—graphic works that critique both Spain’s culture and humanity in general. Throughout the series, Goya makes trenchant political commentary and references to witchcraft accompanied by bizarre and disturbing imagery.

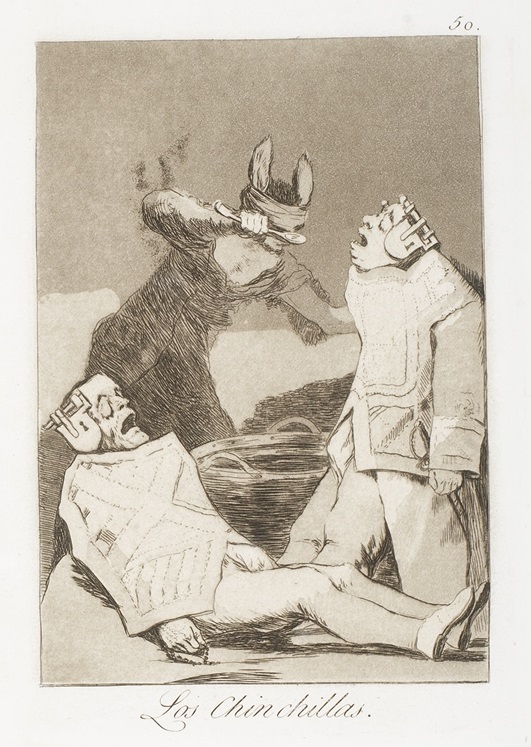

The “Caprichos” etchings were considered so horrific by some that their impact on society can still be felt today. Case in point: The two human figures from Goya’s 1799 “Caprichos” etching titled “Los Chinchillas” were actually used as the inspiration for Boris Karloff’s iconic makeup in the 1931 film “Frankenstein.”

To give you a better idea of Francisco Goya‘s beautifully dark sensibilities, here are 7 of the most undeniably eerie etchings from his acclaimed “Los Caprichos” series.

As an added bonus, we’ve included Goya’s commentary on the symbolism and significance of each image—taken from the artist’s own “Prado manuscript.”

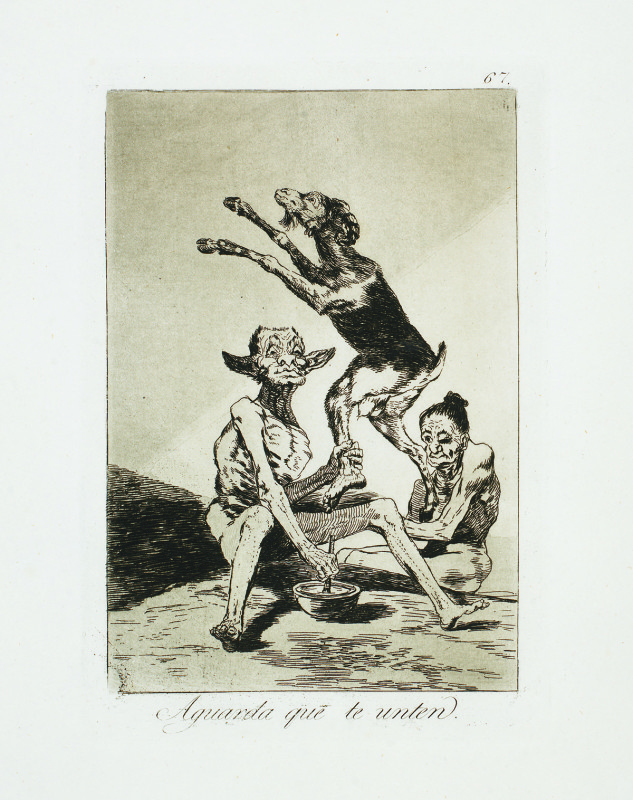

Aguarda que te Unten

(Wait till you’ve been Anointed)

c.1799

This image shows a goblin and an old hag, possibly about to sacrifice a goat. While the two figures are creepy enough, perhaps the true horror is that the goat’s leg held by the goblin ends in a human foot.

From the Prado manuscript: “He has been sent out on an important errand and wants to go off half-anointed. Even among the witches, some are hare-brained, impetuous, madcap, without a scrap of judgement. It’s the same the world over.”

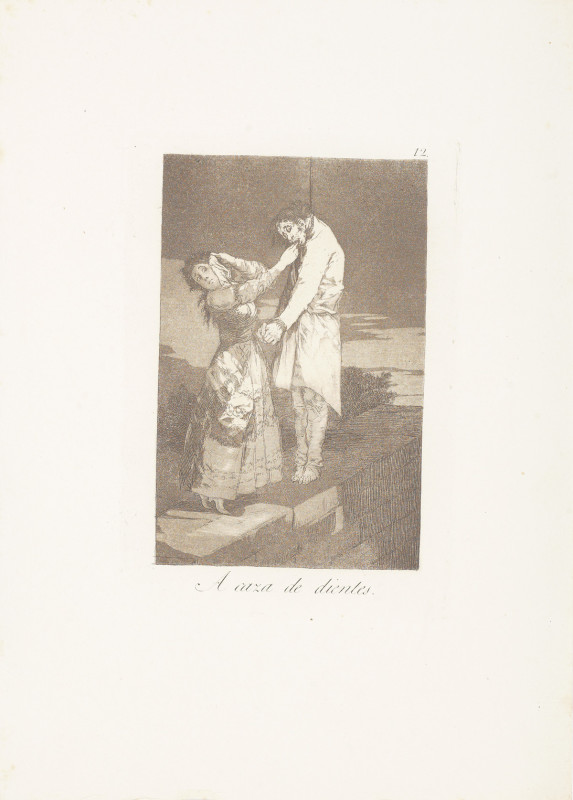

A Caza de Dientes

(Out Hunting for Teeth)

c. 1799

Witches need to collect their spell and potion ingredients from somewhere, right? Apparently, that sometimes involves prying teeth from a dead man, which, as this image shows, is a grotesque errand.

From the Prado manuscript: “The teeth of a hanged man are very efficacious for sorceries; without this ingredient there is not much you can do. What a pity the common people should believe such nonsense.”

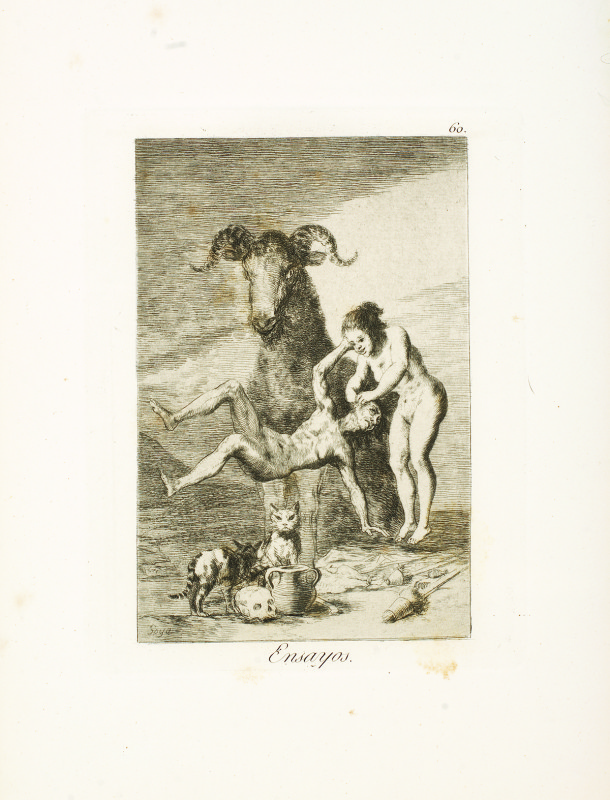

Ensayos

(Trials)

c.1799

This appears to be a witch, shown torturing a man while a demonic goat watches. Though open to interpretation, the manuscript hints at this witch learning sorcery, demonstrating just how far people will go to earn money or power.

From the Prado manuscript: “Little by little she is making progress. She is already making her first steps and in time she will know as much as her teacher.”

Buen Viage

(Bon Voyage)

c.1799

We watch as a terrifying winged creature takes flight with numerous wailing heads on its back. As the manuscript suggests, there is little doubt people would be frightened by this monster.

From the Prado manuscript: “Where is this infernal company going, filling the air with noise in the darkness of night? If it were daytime it would be quite a different matter and gun shots would bring the whole group of them to the ground; but as it is night, no one can see them.”

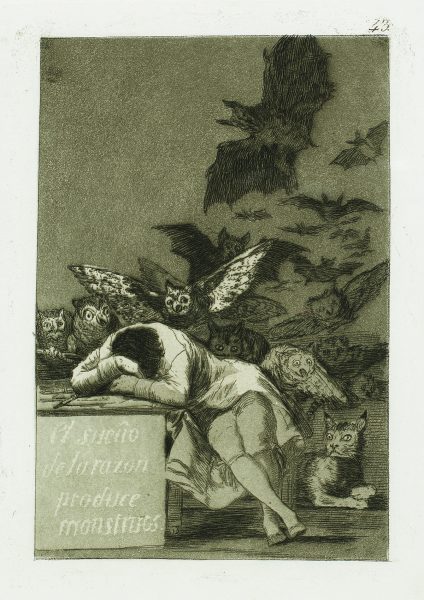

El Sueno de la Razon Produce Monstruos

(The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters)

c. 1799

“El sueno de la Razon produce Monstruos” (The sleep of reason produces monsters) (c. 1799). Etching from Francisco Goya’s “Los Caprichos” series.

Perhaps the most iconic work from “Los Caprichos,” the sleeper is actually Goya himself. Large owls and bats flutter around the artist while a huge witch’s cat watches on. Goya’s reason is dulled by sleep and “bedeviled by creatures that prowl in the dark,” according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From the Prado manuscript: “Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders.”

Donde va mama?

(Where is mother going?)

c. 1799

A witch is carried aloft and escorted by odd, goblin-like denizens. The creep factor is somewhat muted by the absurdity of the image, especially the cat desperately clinging to the parasol, but still, is this a mother you want to run into?

From the Prado manuscript: “Mother has dropsy and they have sent her on an outing. God willing, she may recover.”

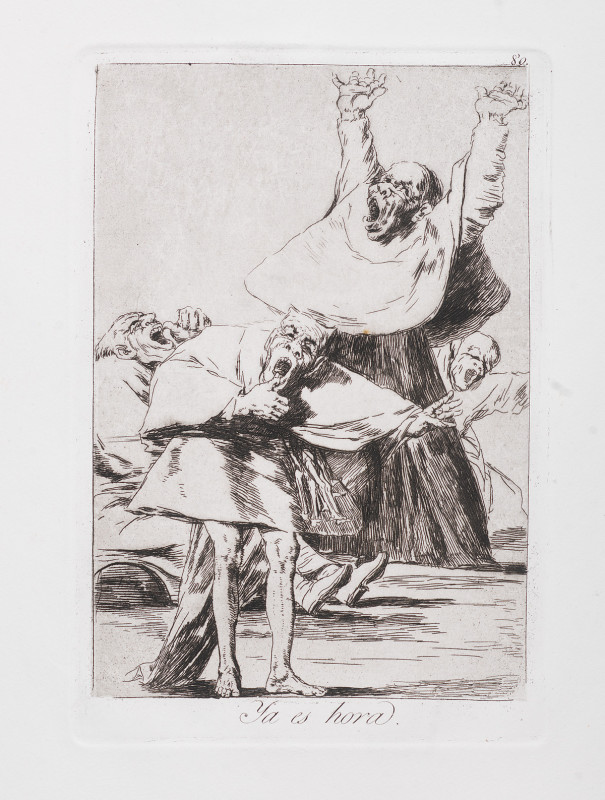

Ya es Hora

(It is Time)

c. 1799

The final installation of Goya’s series is perhaps the most shocking, like the last startling image of a nightmare before waking. Goya blurs reality with fantasy, depicting men in clergy garments with gruesome faces.

From the Prado manuscript: “Then when dawn threatens, each one goes on his way, Witches, Hobgoblins, apparitions and phantoms. It is a good thing that these creatures do not allow themselves to be seen except at night and when it is dark! Nobody has been able to find out where they shut themselves up and hide during the day. If anyone could catch a denful of Hobgoblins and were to show it in a cage at 10 o’clock in the morning in the Puerto del Sol, he would need no other inheritance.”

Interested in learning more or collecting works by Francisco Goya, including “Los Caprichos” etchings? Register for our exciting online auctions or contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654, ext. 4 during business hours or sales@parkwestgallery.com.

You can also see selections from “Los Caprichos” in person at Park West Museum in Southfield, Michigan, just outside of Detroit.

This free-to-the-public museum has works from masters like Picasso, Renoir, and Rembrandt, and includes a gallery devoted to the graphic works of Francisco Goya. You can find more information about visiting the museum here.

We also invite you to watch our “Introduction to the Masters” video where Park West Gallery Director Morris Shapiro discusses Goya’s legacy.

In his words, “Goya’s technical virtuosity combined with his amazing storytelling ability and his viewpoint of society of his time changed the course of art history, and Goya is considered by many to be the first modern artist.”